They say "The journey of a thousand miles starts with a single step.” For me, it wasn't a step, but rather my head hitting my computer keyboard. Literally. It was a late night in April of 2013. I had just had a hard night putting my two young children to bed while my husband, who is also an architect, was away at class. He had started law school just one month before our daughter was born, so I was used to having the kids alone at night. But this night in April was harder than normal because I had a deadline at work. I had to be home with my kids while my team diligently worked away AT work. So after I got the kids in bed, I logged in from home and started working. But of course Revit doesn't work as smoothly when you connect remotely and something went wrong. I honestly don’t remember what happened, but my head hit the keyboard and the tears started flowing.

I thought to myself ‘There has to be a better way. I can’t be the only one struggling with this’. And by ‘this’, I meant the struggle that any parent has with this delicate dance between work and home. Since my Revit model was somehow paralyzed, I decided to search for some resource in the Twin Cities. Was there some sort of support group, or network of mothers or parents working in architecture? Nothing. I did find a lot out there, but nothing in Minneapolis, MN. By the end of that night, I knew what I had to do. I knew I wasn't alone in this struggle; I had to start some sort of Women in Architecture group.

Fast forward to July of 2014. With the help of many talented women, we had successfully started a Women in Architecture Committee with the AIA Minnesota. We had also started Women in Architecture + Design- Twin Cities, which is an inclusive community-based group. The AIA WIA Committee submitted a presentation for consideration to the AIA Minnesota Convention and it was accepted. The following is a summary of the presentation I gave to set up a panel discussion with women leaders in Minnesota. There were so many contributors to this presentation, but one woman- Samantha Turnock Mendiola deserves particular thanks and praise. Samantha designed the entire presentation and was my much needed sounding board, and so often, my reality check in developing the presentation.

The seminar is organized into 4 sections: TRENDS, ROOT CAUSES of what is holding women back or causing them to leave the profession, the BUSINESS CASE and finally CONCRETE MEASURES firms can take to help attract, retain and raise women into leadership roles. Here’s what we found:

Trends:

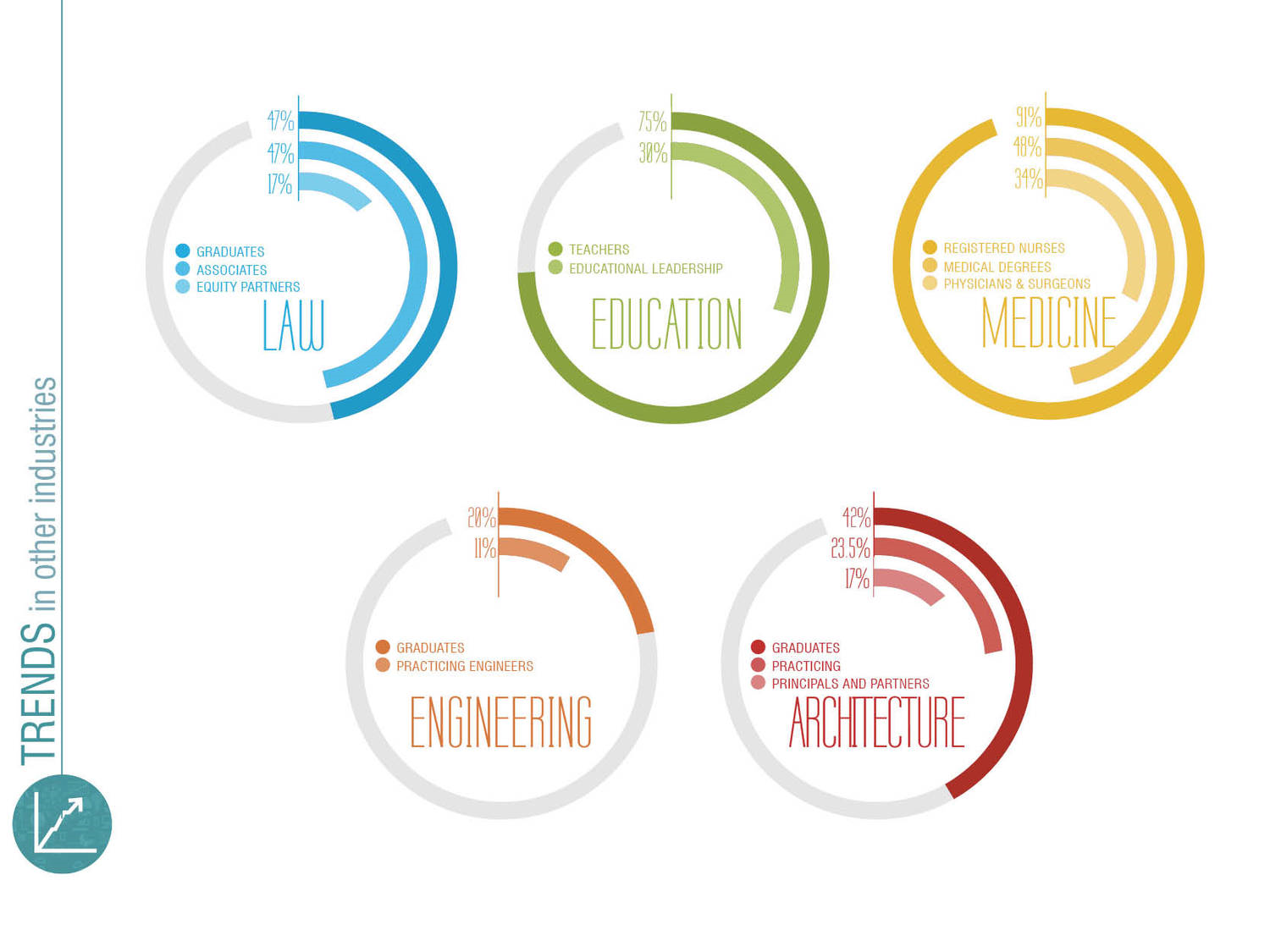

First let’s have a look at where we are today. Today women comprise 42% of graduates from architecture schools. The number of women interns that register with NCARB falls only slightly to 39%. But then, only 30% of women are Associate AIA members. Nationally, only 23.5% of people working in architecture are women (this number is from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, so it includes licensed and non-licensed women working in the profession). AIA membership falls even further to 20%. And finally, only 17% of our principals and partners are women. Compared to 42% of graduates.

Sources: Available upon request

So why are those numbers so disparate? I know what you’re thinking… those 42% of women graduates have yet to reach leadership positions- we just have to give them time…. this is a pipeline issue. But actually, we’ve been graduating at or near 40% for a long time nationally, and locally here at the U of M we’ve been at that level since the mid-1990’s.

If we look at the number of women practicing architecture according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics over time, you see a similar trend. The local data shows some promise- the number of women licensed in the state of MN has been steadily growing.

Nationally our AIA membership has had excellent growth recently- you can see it starting in the 1980’s, and today the AIA MN has 24.6% women, which is in line with national numbers.

We’ve seen promising growth in the college of fellows as well- this graph starts in the 1950’s.

This year Julia Morgan won the Gold Medal at the national level- the first woman to ever do so, and Julie Snow won it here in MN- the second woman to ever do so. Overall, AIA Young Architect Awards winners are 25% women, and that percentage is slightly higher in Minnesota.

Let’s have a look at role models young women have today in Architecture School. Currently on average, 30% of people teaching are women, while only 23% of University Leadership positions are held by women.

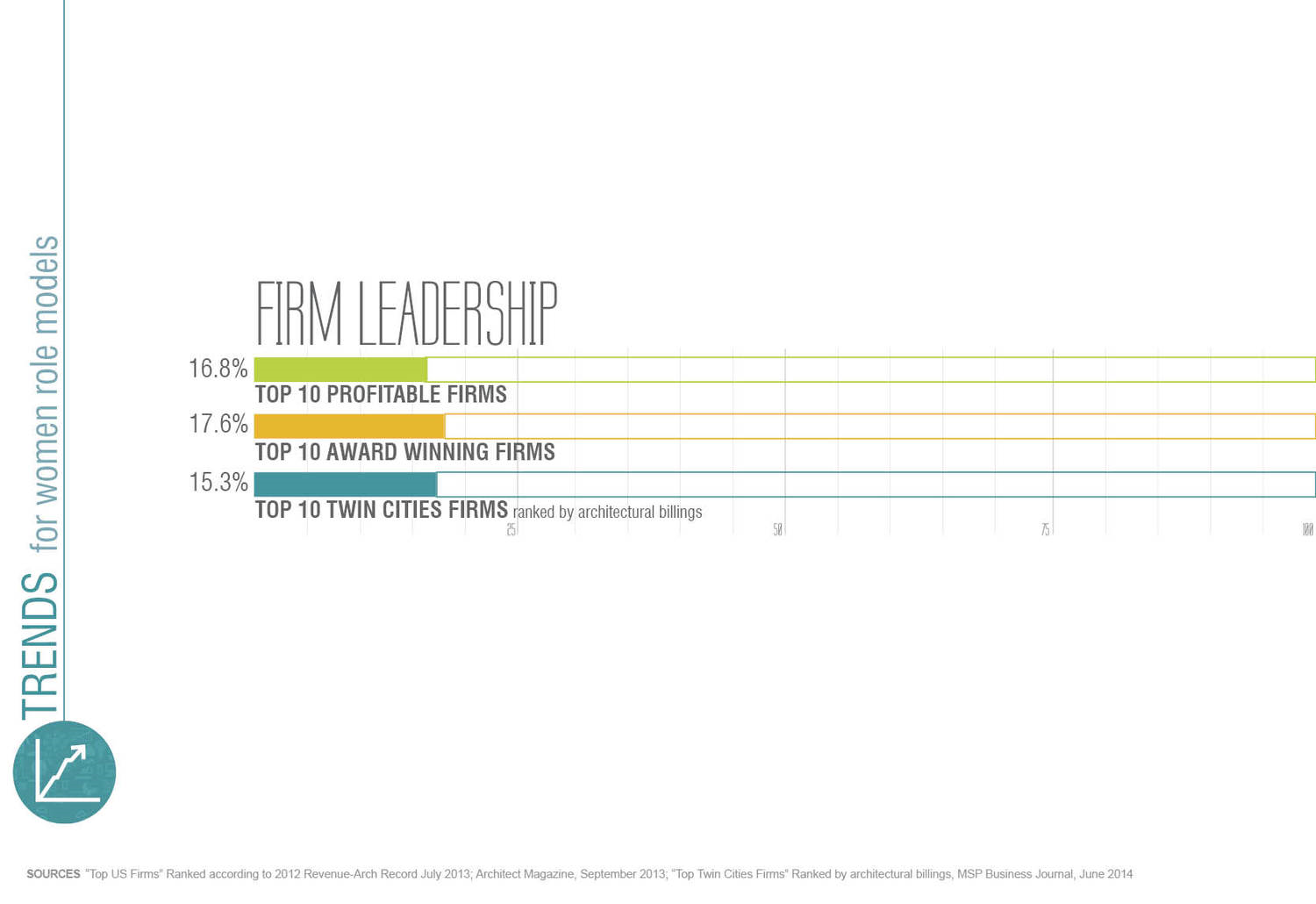

What about in firms? Well, according to rankings in publications like Architectural Record, you can see below the rankings of the top profitable firms, the top award-winning firms, and the top firms here in Minnesota. There just aren't a lot of women role models out there.

And it turns out we’re not unique in our profession. Here is how Law, Education, Medicine, Engineering and Architecture stack up. Architects aren't the only ones facing these issues.

Sources: Available upon request

Root Causes

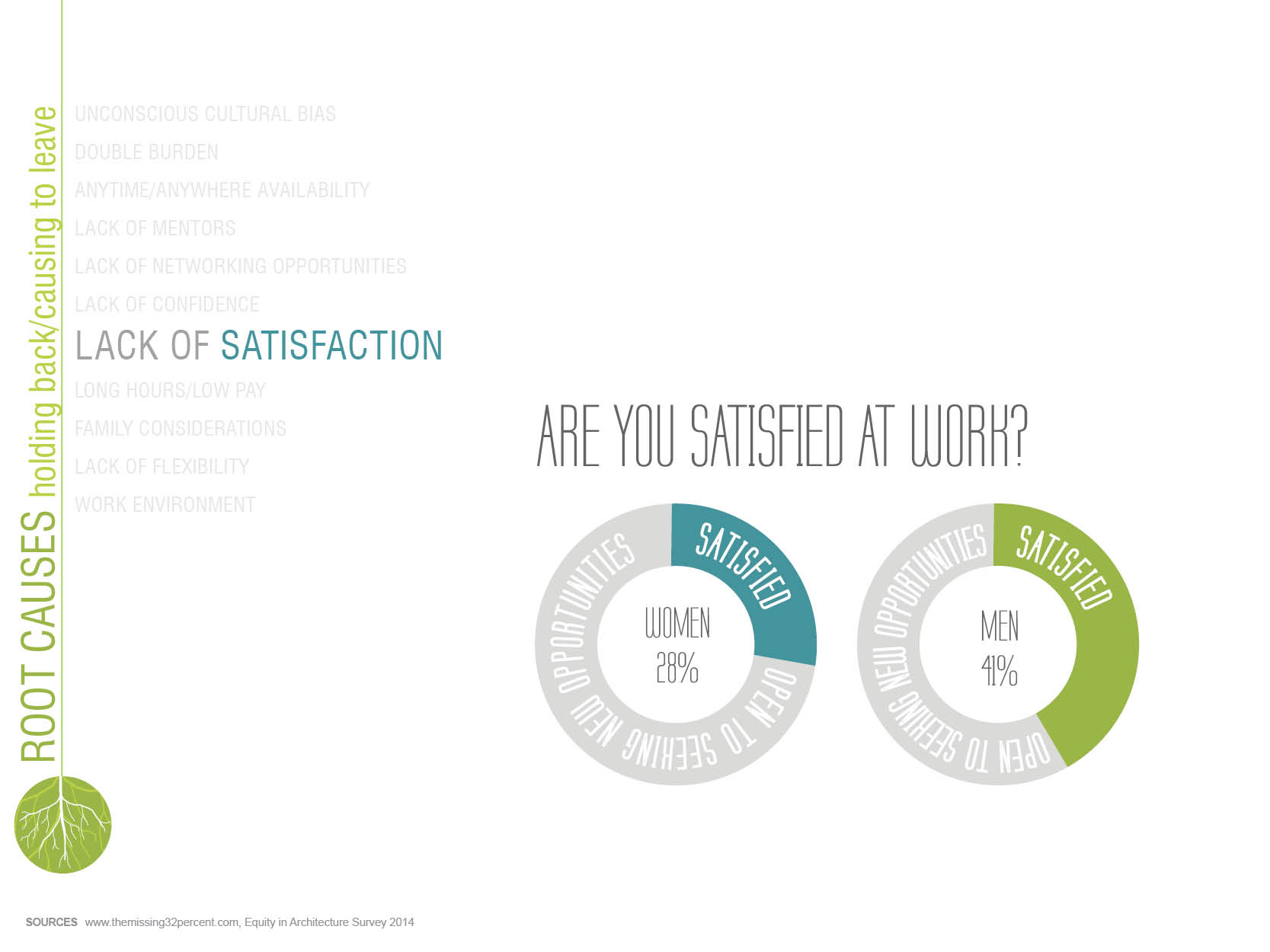

Next let’s have a look at the list of what holds women back (above the line), and what causes women to leave the profession (below the line). (Note: The Double Burden is working full time and then also doing the majority of housework and child care).

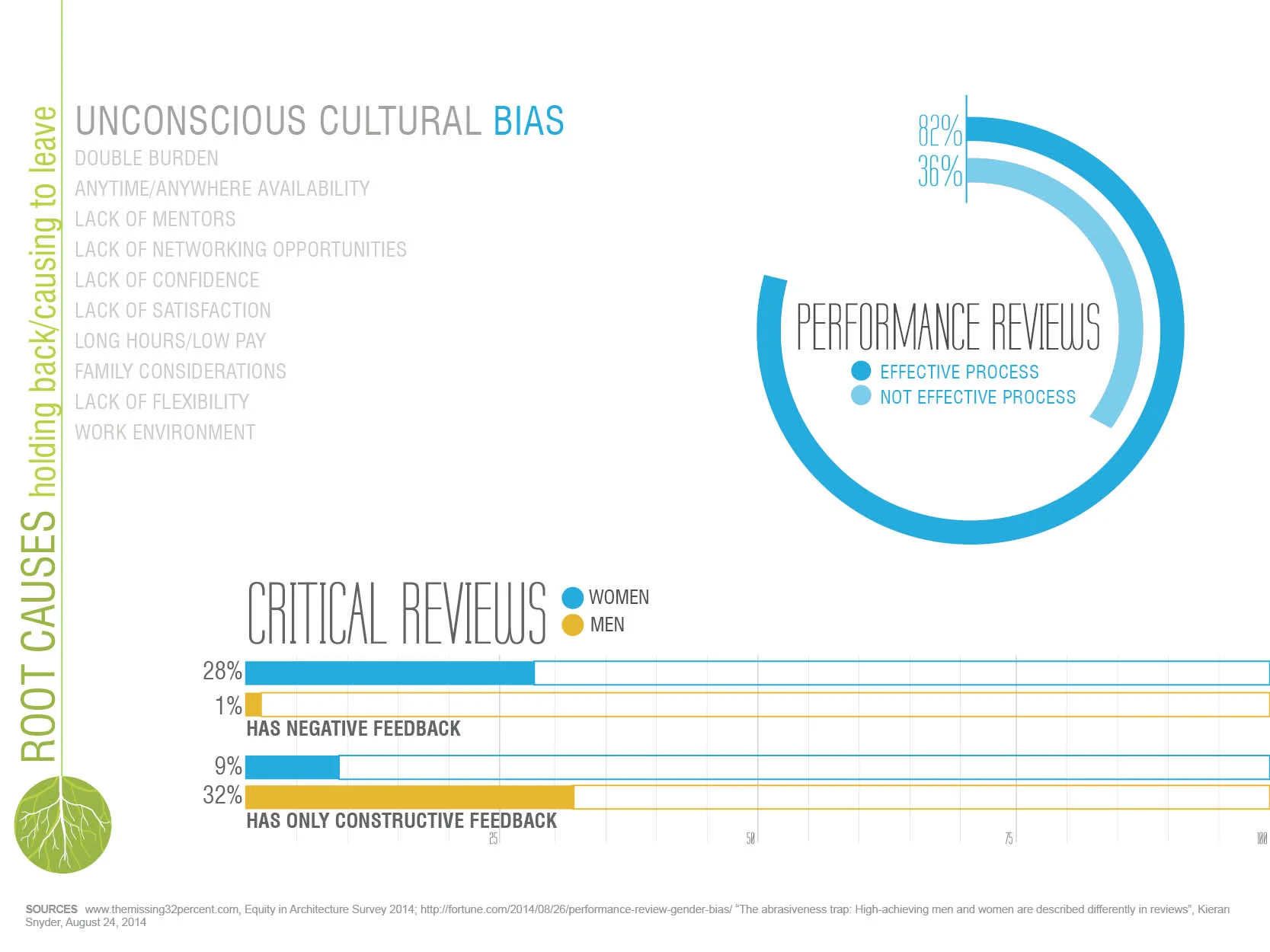

Let’s start with unconscious cultural bias. We all have them- men and women alike. In The Missing 32% Project's recent survey, when asked “What is the best criteria for promotion?”, the top criteria was performance reviews, with 82% of people saying it is an extremely effective process. And yet, in another study of performance reviews, women received significantly more negative feedback than men, and men’s reviews more often include only constructive criticism. Now women’s reviews did include constructive criticism, but they also included personality criticism’s that were absent in men’s reviews, with words like abrasive, bossy, aggressive and emotional.

So let’s have a look at a blind study conducted by Yale University. 127 professors of science were sent application materials for a lab manager position. Half got a resume with the name John, and half got the same resume with the name Jennifer. John was rated higher in competence, hireability and mentoring- totaling a 4.0 out of 7, where Jennifer scored only 3.3 out of 7. And when it came to the salaries they were offered? John was offered over $30,000, whereas Jennifer was only offered $26,507. It was the same resume, and John’s salary was 14% higher- because his name was John and not Jennifer.

This reaffirms a statement made in one McKinsey report "Women Matter" : men tend to be promoted based on future potential, but women tend to be promoted based on past performance. I’m going to say that again because it’s really important. Men tend to be promoted based on potential, and women based on performance.

Let’s move on to lack of mentors: "Like" tend to mentor "Like". People tend to mentor someone who behaves, thinks and has qualities most like themselves. So men tend to mentor men. This becomes a problem because there simply aren’t women in senior positions to mentor young women. Also, there can be reluctance among men to mentor young women because of the perception that it may appear inappropriate. All this adds up to a scarcity of mentors for women.

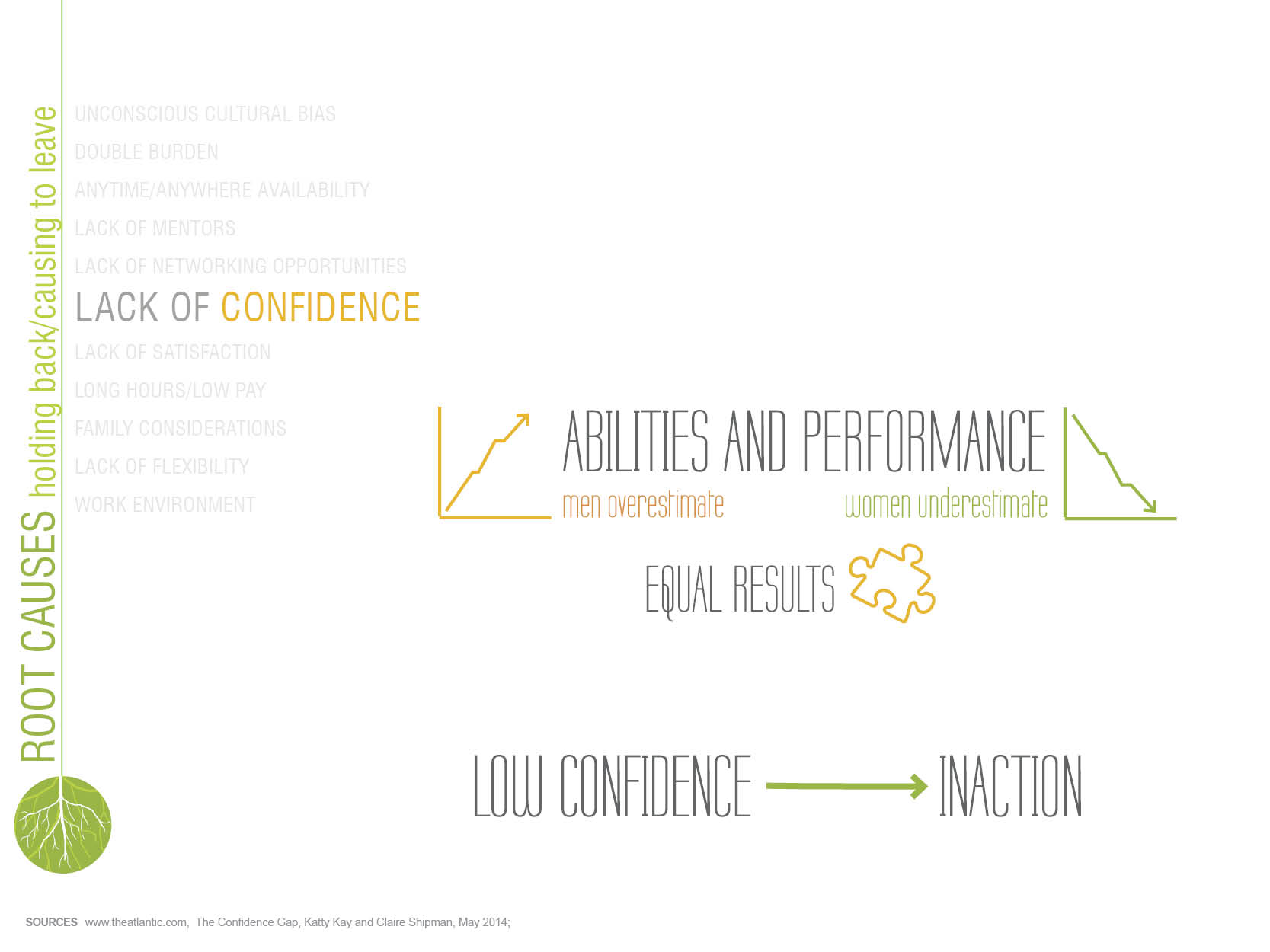

Now onto the confidence conundrum. In numerous studies, men tend to overestimate their abilities and performance, while women tend to underestimate both. But their job performance did not differ in quality. This has been shown in study after study. But what lack of confidence ultimately results in is inaction. In one study exemplifying the results of inaction, 500 students were given a series of spatial puzzles to solve, and the men performed markedly better than the women. The researchers were shocked, and wanted to find out what caused the disparity. It turned out that a number of women simply didn’t attempt many of the puzzles. So they decided to try it again, but this time they said that everyone had to at least try to solve all the puzzles. And the men and women performed equally. Women tend to hold themselves back because an outcome of low confidence is inaction.

Its also worth noting another result from The Missing 32% Project's survey, which is one of the reasons why women and men leave the profession: a lack of satisfaction. Only 28% of women responded being satisfied and not looking for other opportunities, compared to 41% of men being satisfied.

Business Case:

Let’s move onto the business case for retaining women in architecture. There are studies that show that gender diversity improves employee engagement, retention and recruiting. A more diverse employee base better reflects our diverse client base. But today we’re going to focus on just the last two.

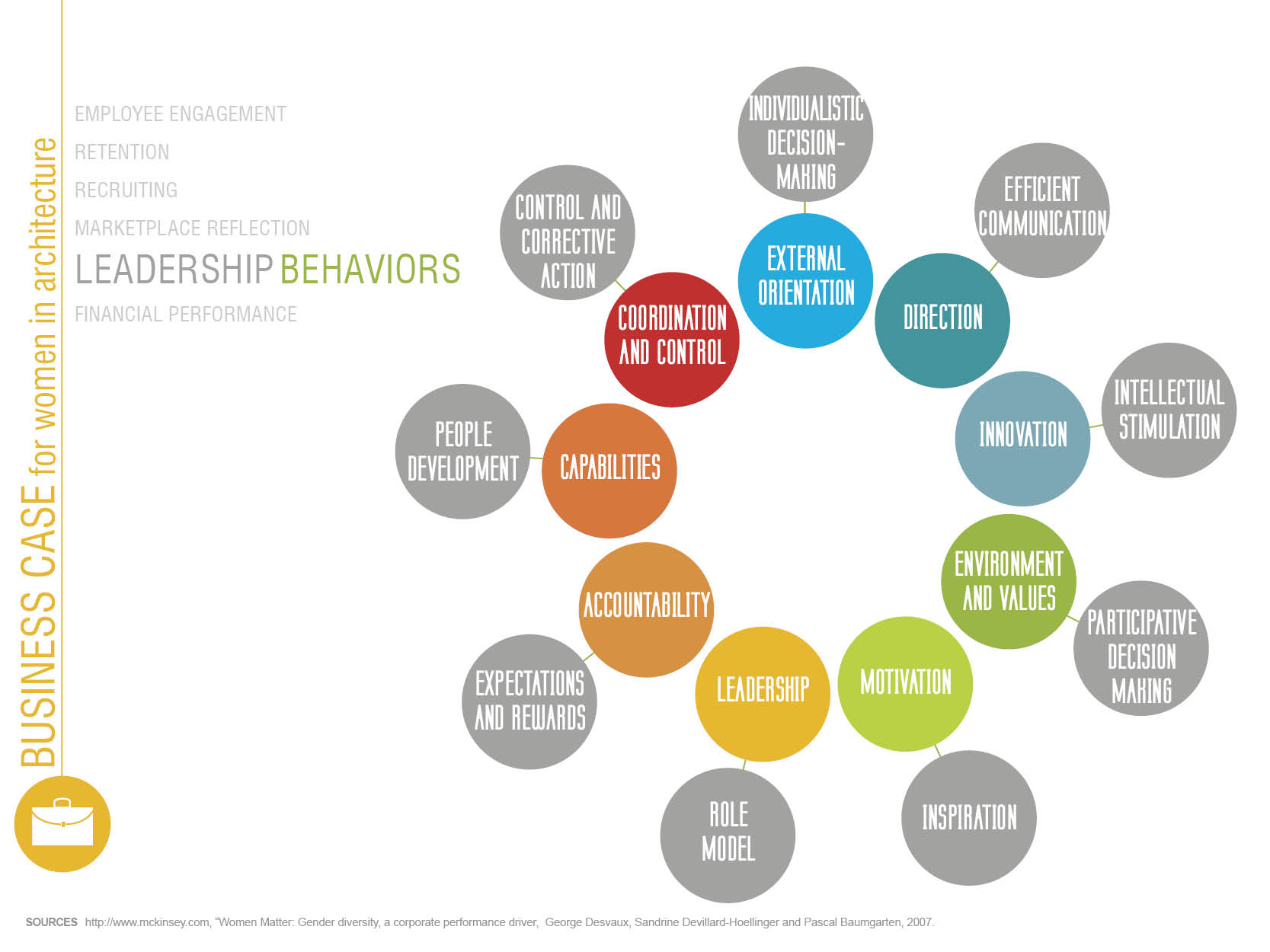

First let’s address leadership behaviors. In a report titled "Women Matter: Gender Diversity" McKinsey developed a tool to measure the operational excellence of a business. They outlined nine criteria, you can see them listed below, and companies that performed the highest in these 9 criteria saw greater financial success. But we’re going to get into the financial piece in a bit.

They then took these 9 criteria of organizational excellence, and associated them with leadership behaviors that improved the outcomes of the 9 criteria. So you can see at the top in the red circle, coordination and control is improved by control and corrective action, and capabilities in the orange circle is improved by people development and so on.

They then looked at how often these leadership behaviors are exuded by men and women. Two of them men and women apply equally (grey): Intellectual stimulation and efficient communication. Men apply two behaviors more (green): individualistic decision making, and control and corrective action. Women, however, apply five of these behaviors more than men (blue): people development, expectations and rewards, role model, inspiration and participative decision making. Now when we tie these behaviors back to the organizational excellence, you can see that having a diverse leadership team is a huge advantage.

Because companies that score high in organizational performance financially perform more than twice as well than companies that score low in organizational performance.

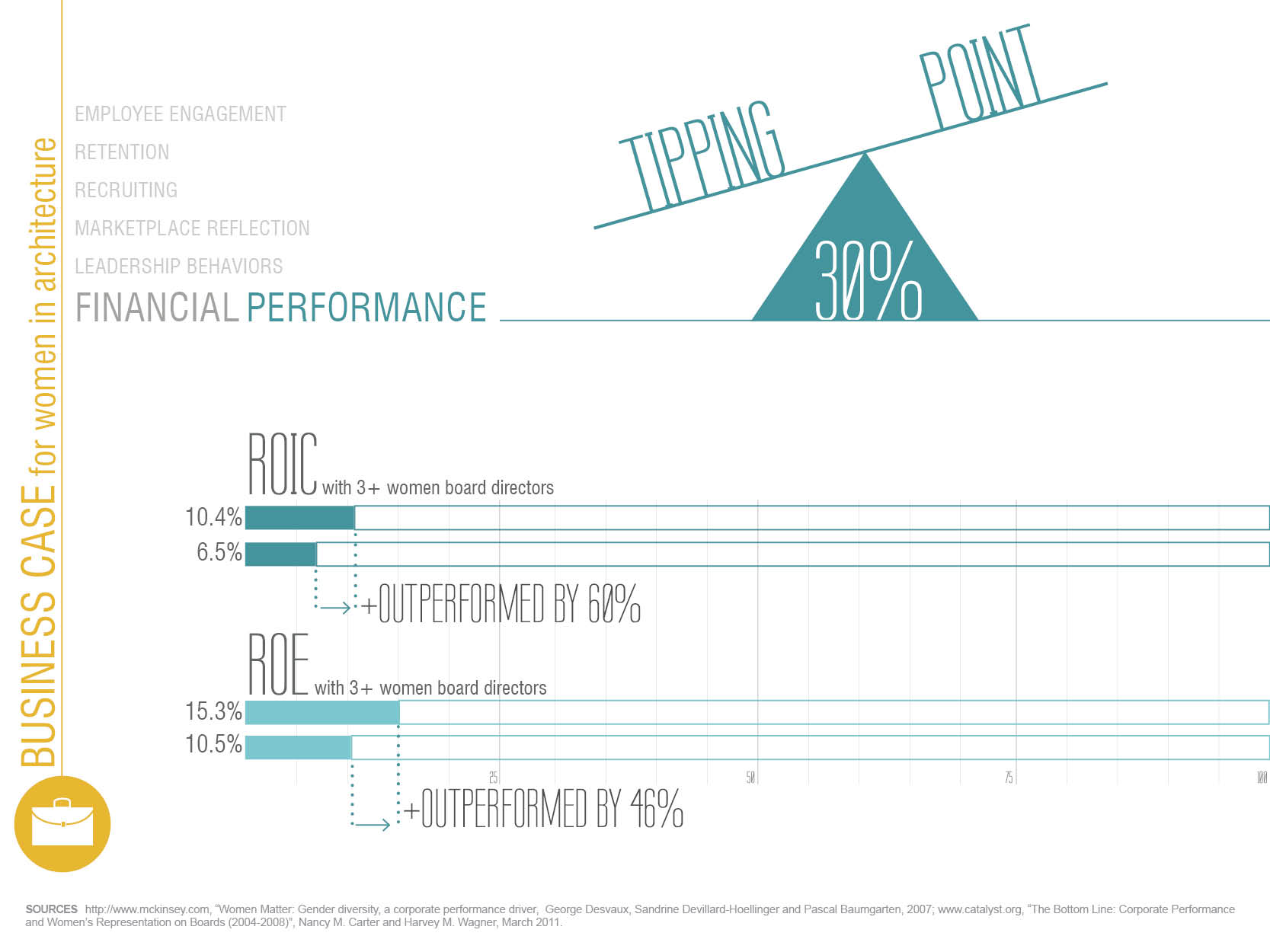

While this was one tool used to measure financial success, it has been shown in study after study that companies with a higher proportion of women in top management perform better.

It’s worth noting however, that having one woman on your board will likely help, but there does seem to be a financial tipping point at about 30%. The financial performance of boards with 30% women or higher have been shown to perform anywhere from 40-60% better over time than boards with no women.

Concrete Measures:

So what measures can firms take to better support, retain and advance women into leadership roles? Well, there are lots of things!

Again, I’ll just address a few. The first thing is to simply be aware. It turns out there are a lot of men that don’t know many of the challenges that women face. So simply becoming more in-tune with some of these issues is a huge step. One way to better understand these challenges is to know the data in your firm. Conduct a poll, and ask women the challenges they face. Run the numbers- know the percentages of women at each level of your firm. Then be sure that whenever possible, you are considering diversity and inclusion. If you are hiring, try to interview both men and women for the position. Continuously monitor your progress. It turns out that firms with a clear understanding of their starting point are more than twice as likely to succeed at implementing diversity measures. Define what success looks like for your firm, and measure how far you've come each year.

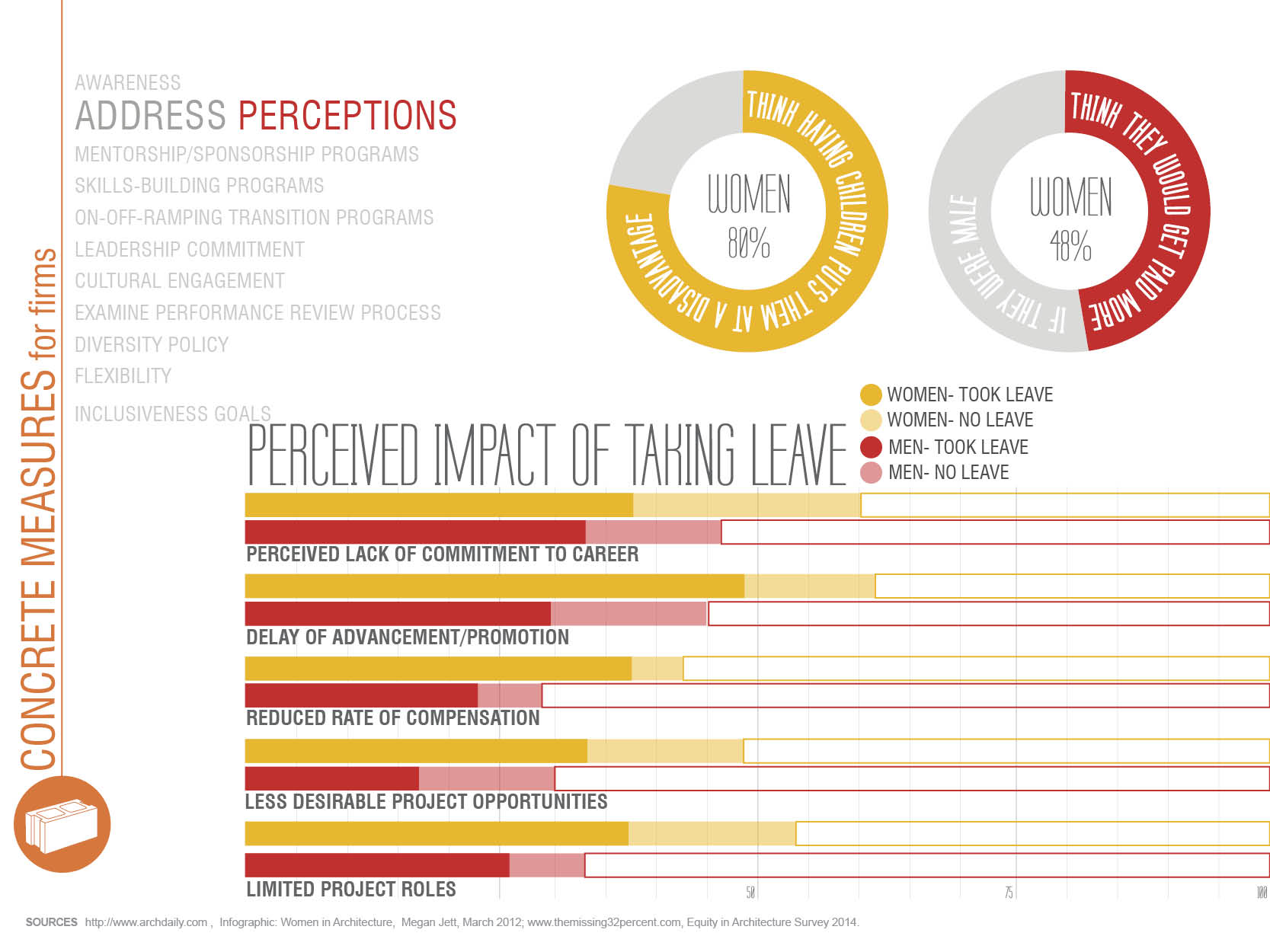

The next thing firms can do is identify and address perceptions. As shown in the The Missing 32% Project's Equity in Architecture survey, the perceived impact on your career of taking leave was higher than the reality in every category. And did you know that 80% of women in another survey of architects believe that having children puts them at a disadvantage? And in that same survey 48% of women thought they would get paid more if they were a man? These are all perceptions that can easily be addressed, and firms that address these underlying attitudes are 4 times more likely to see meaningful change. (Please note: I am keenly aware that it is a fact that women are paid less than men, and not merely a perception. However if firms address the perception by gathering the hard data, they will then have the evidence and will be obligated to address the issue).

Another very important issue is clear leadership commitment. Diversity measures will not succeed without top-down support. Leadership needs to both acknowledge and visibly value diversity. This can be accomplished by making diversity a business and strategic imperative. Simply add it to your business plan.

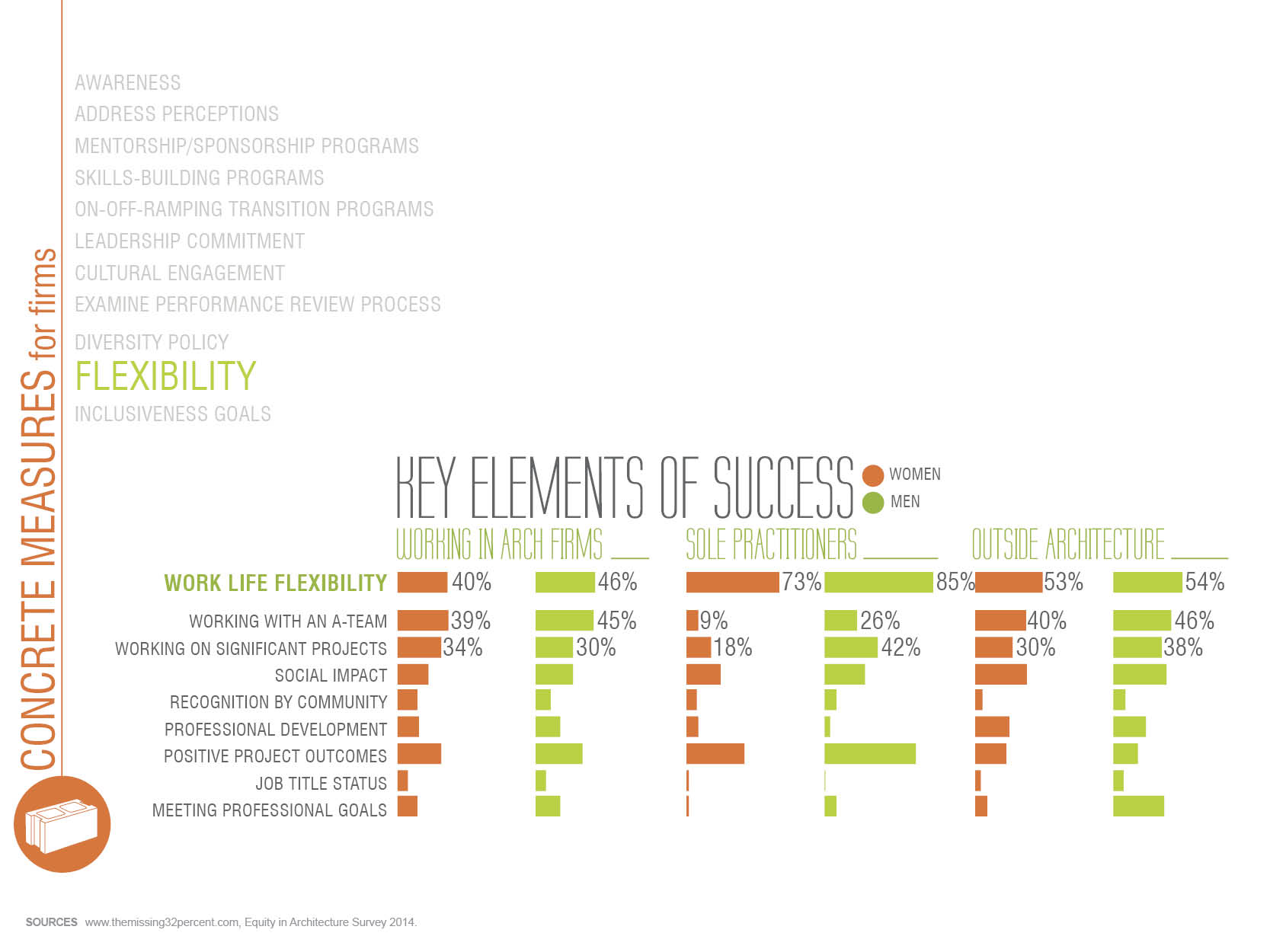

And finally, allow for flexibility. In The Missing 32 Percent's survey, work/life flexibility was a key element of defining success for men and women in large and small firms. Flexibility is likely the most important, and easiest concrete measure firms can implement. This could mean flexible start and end times, flexibility of working from home, working part time or even allowing people to set their own hours.

In Conclusion:

I’d like to challenge each and every one of you to take action, no matter how large or small, to help advance women in our profession. To the men: you comprise over 75% of our profession. If we are to see meaningful change, it must include you. If you don’t know what you can do, then ask. Ask me, ask Rosa, ask a Women in Architecture Committee, but I assure you, the solution to these issues involves you. To the women in the room: I encourage you to get involved, to speak up and to advocate for the advancement of women into leadership roles. We have come a long way, but we still have work to do. I am convinced that women and men together will bring about meaningful, positive change for Equity in architecture, thereby creating a strong and enduring profession, with a vibrant future ahead of us all.

Following the presentation, the panel discussion included Michelle Mongeon Allen- COO of JLG Architects, Renee Cheng- Associate Dean of the College of Design at the University of MN, and Julie Snow of Snow Kreilich Architects and recipient of the 2014 AIA MN Gold Medal Award. The discussion was rich- below are a few quotes:

Julie Snow said the number of hours you spend at your desk doesn't necessarily translate to good performance. “I think we have to disabuse ourselves of the idea that hours equal productivity,” she said. “It’s not true.” Julie also said “The cool thing about Minnesota is they gave the Gold Medal to two women while they were alive!”, and “We need to embrace diversity in order to stay relevant”. From Renee Cheng, we heard “It’s not really on women to go fix themselves, but it’s [up to] the organization to be aware of this and to realize that they have actively participated in this disparity.” And Michelle Mongeon Allen stated that the industry is losing an opportunity if it’s overlooking a big segment of the population. “Those are people that could grow my company. To me, that is the business case.”

The response to the seminar was overwhelmingly positive, and we are already looking to build on the work and research we have already conducted. The conversation has long since begun on equity in the architectural profession, now it’s time for action. This seminar was one more step in our journey- or one more bite out of our whale. We are making progress, and we are starting to see meaningful change by raising awareness. Let’s keep the momentum going, and continue to take action. We will see meaningful change in this generation, and together, we will make a positive impact on our profession and the world around us.

Written by Amy Kalar, AIA