by Annelise Pitts - Assoc. AIA

When describing the gender wage gap, we often hear basic comparisons of men’s and women’s average salaries, like “Women make 80 cents for every dollar a man makes.” While this is technically accurate, it isn’t the most useful way of describing why there’s a gender pay gap, or what we can do to fix it.

According to Harvard Economist Claudia Goldin, the wage gap is better understood by applying the idea of “equal pay for equal work.” In other words, the wage gap should be quantified as the difference in men’s in women’s salaries after we’ve controlled for differences in work setting, job function and responsibility, experience level and training. These “apples to apples” comparisons show that much of the gender pay gap can be explained by differences in men’s and women’s work settings, schedules, roles, and responsibilities.

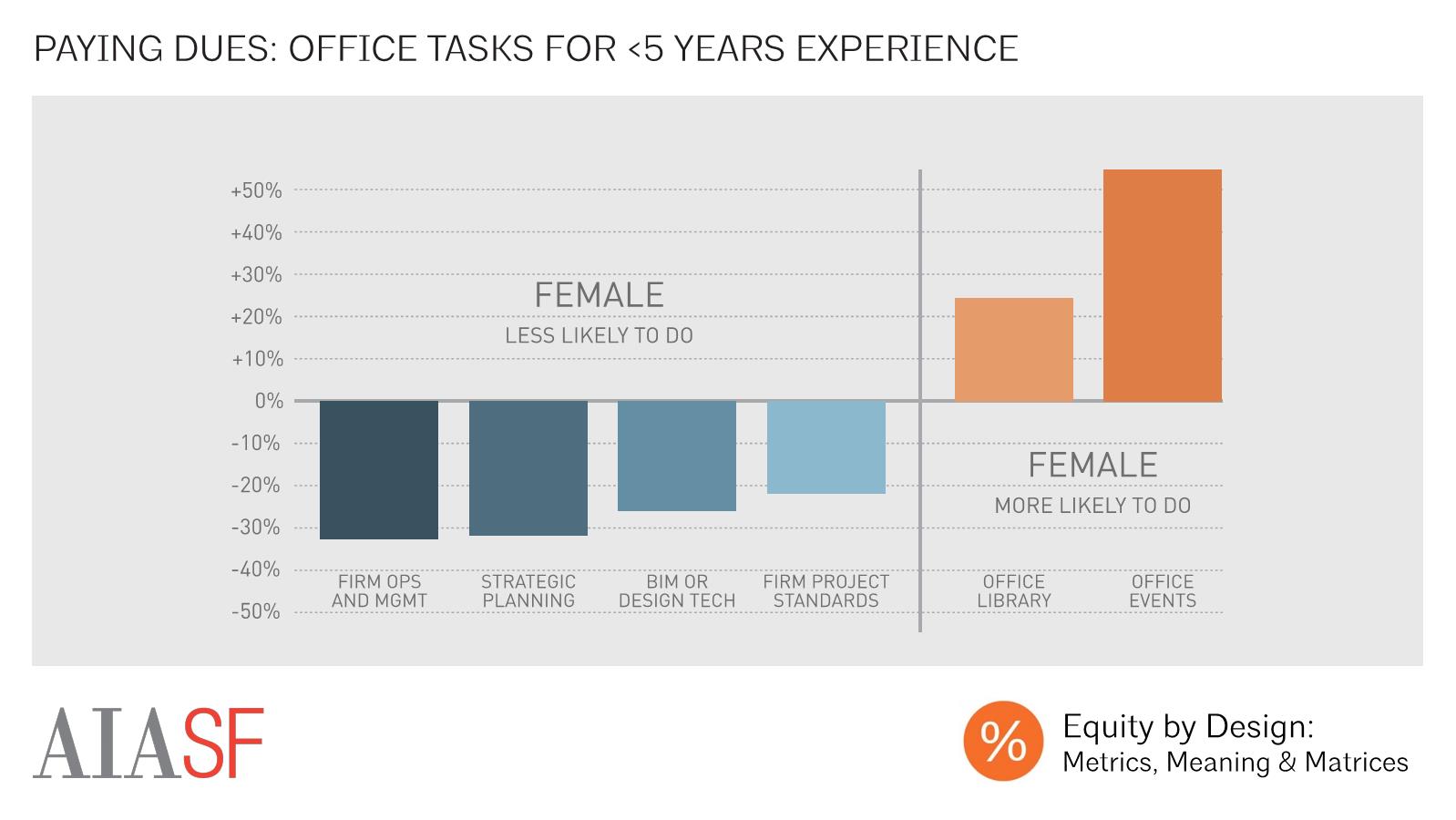

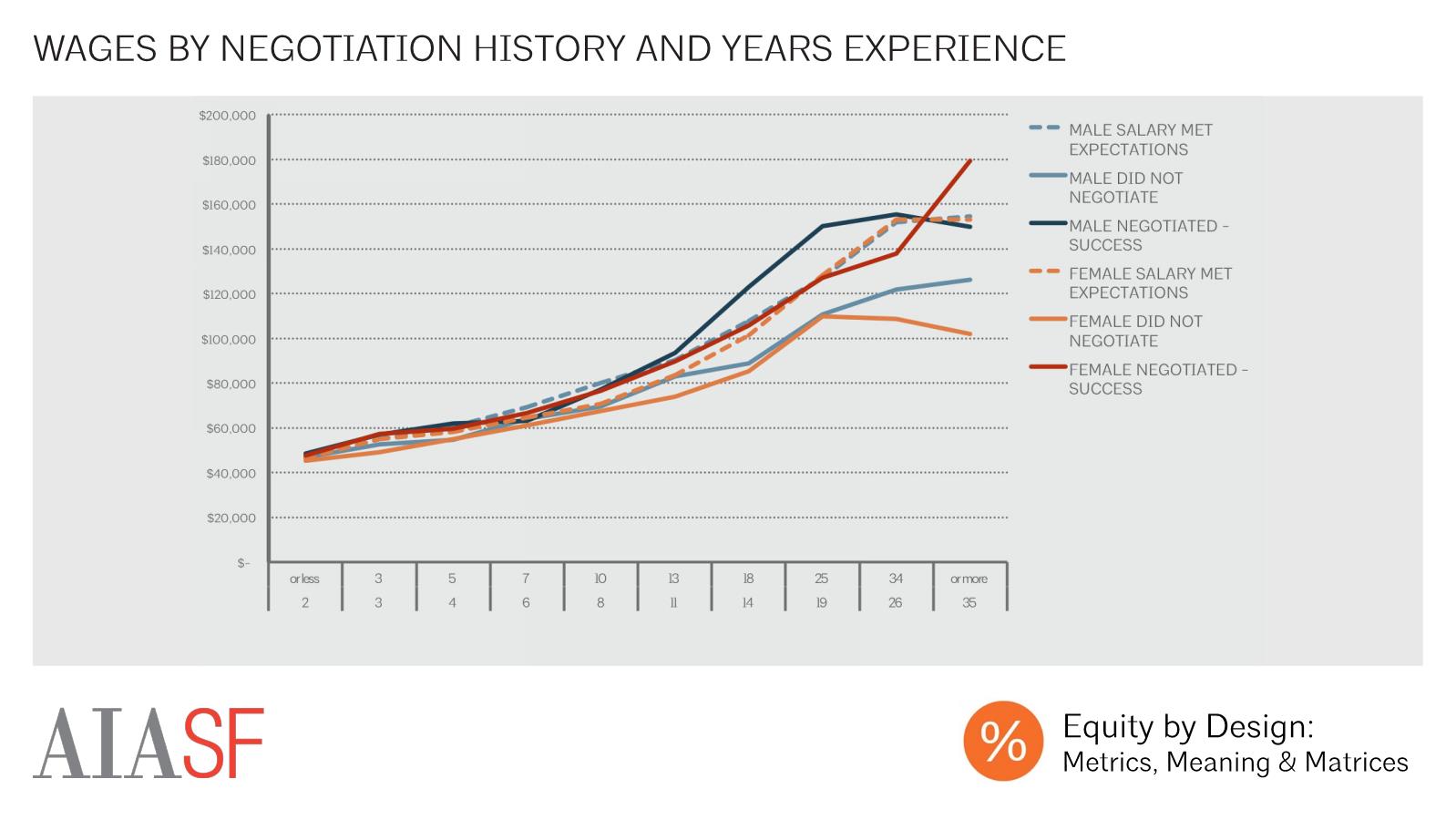

Controlling for these variables (or “correcting” the earnings ratio, according to Goldin) doesn’t show why women would systematically make professional choices that are financially disadvantageous to them. Examining the wage gap through the lens of pay equity, on the other hand, requires us to question these “apples to apples” comparisons further. Do all workers have the opportunity to make professional choices that have been shown to be financially advantageous, and are these decisions rewarded evenly? Do we ascribe inflated value to characteristics of work that are commonly seen as “white” or “male”? Once we’ve seen that differences in pay are directly correlated to differences in how, where and when different demographic groups tend to work, can we rethink the ways in which we ascribe value to work in order to devise compensation systems that are more just?

Goldin’s framework for understanding the wage gap does help to uncover some of the ways in which work seems to valued within our profession. The major drivers of the pay gap can be understood through two forces: Occupational Segregation and In-Sector Differences.

Occupational segregation describes the phenomenon whereby men are more likely to work in high paying industries and while women are more likely to work in lower paid industries. According to Goldin’s research, occupational segregation accounts for only about 35% of the pay gap amongst college graduates, with the other 65% of the gap deriving from in-sector differences, including temporal flexibility. As noted in the first article in the series, this seems to be one of the reasons that women in the “Beyond Architecture” population made less, on average, than men who work outside of a firm setting.

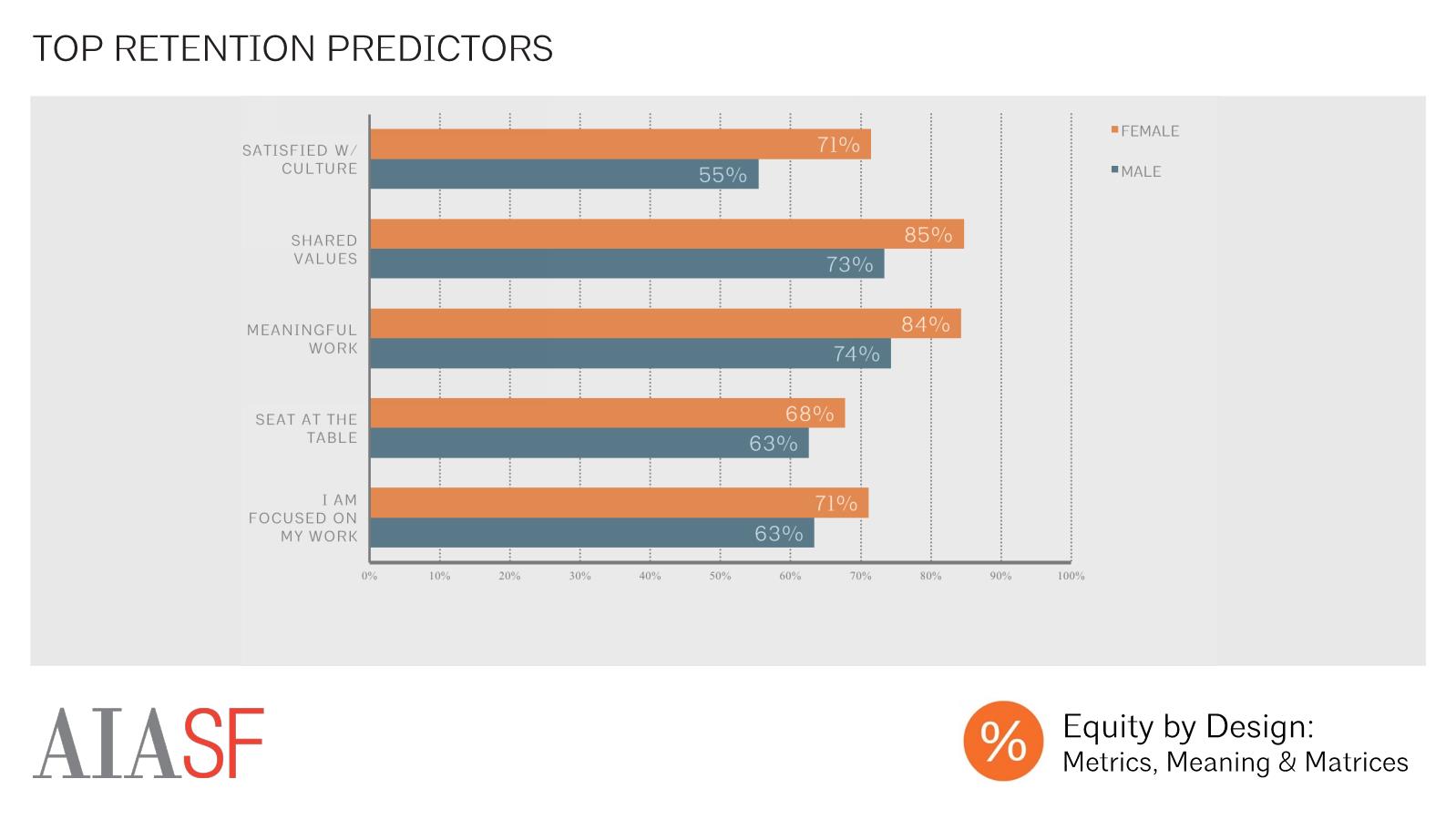

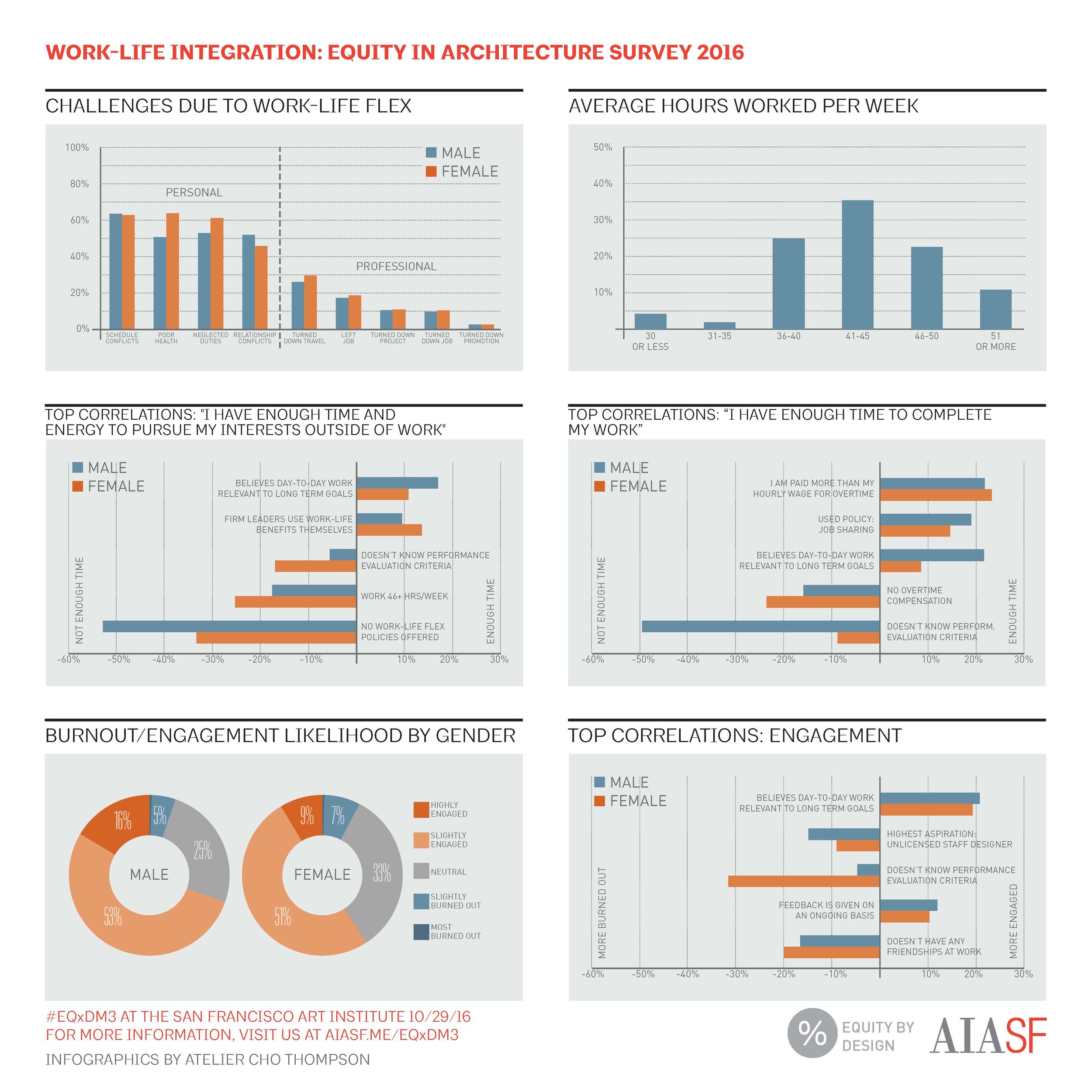

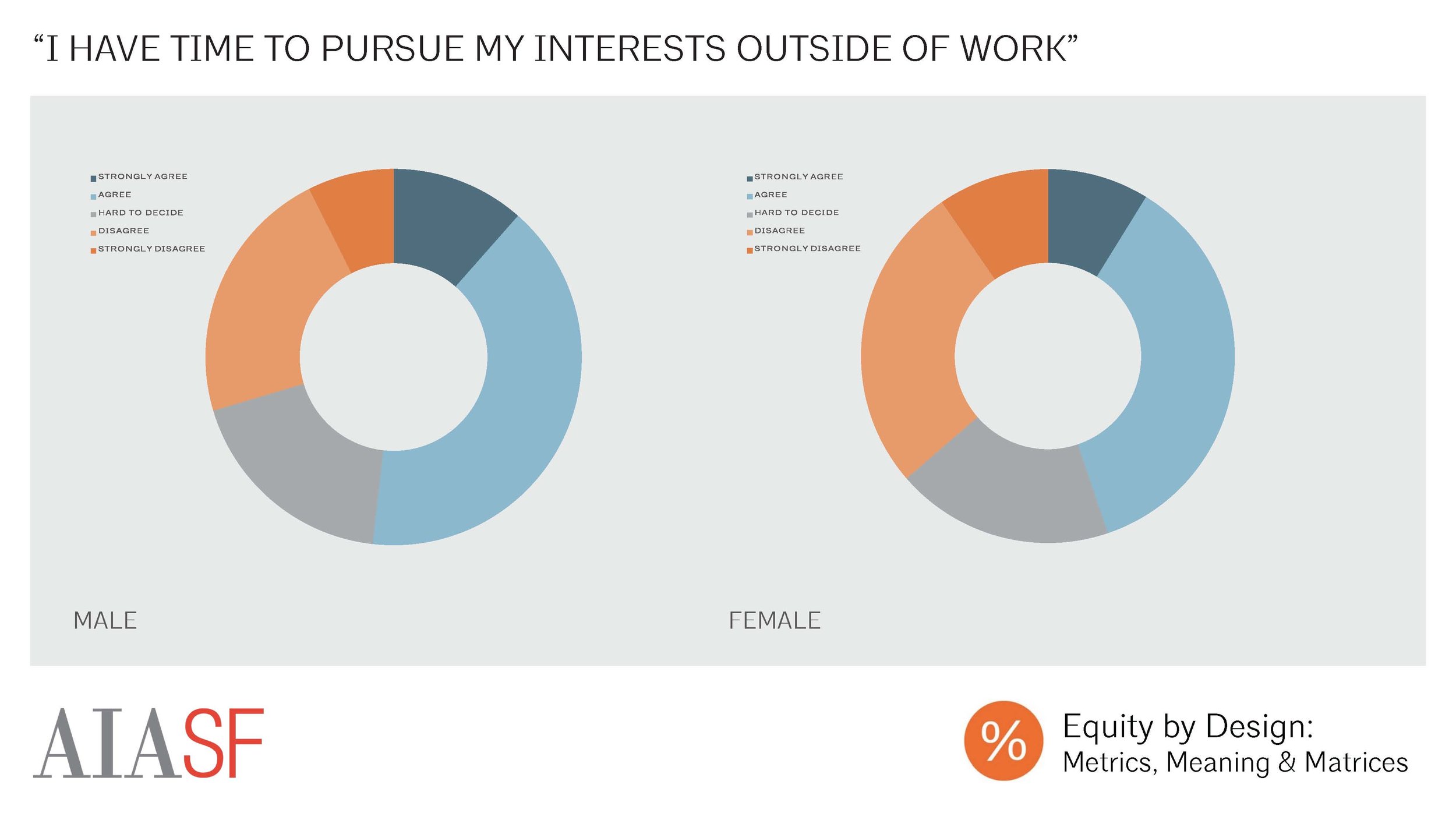

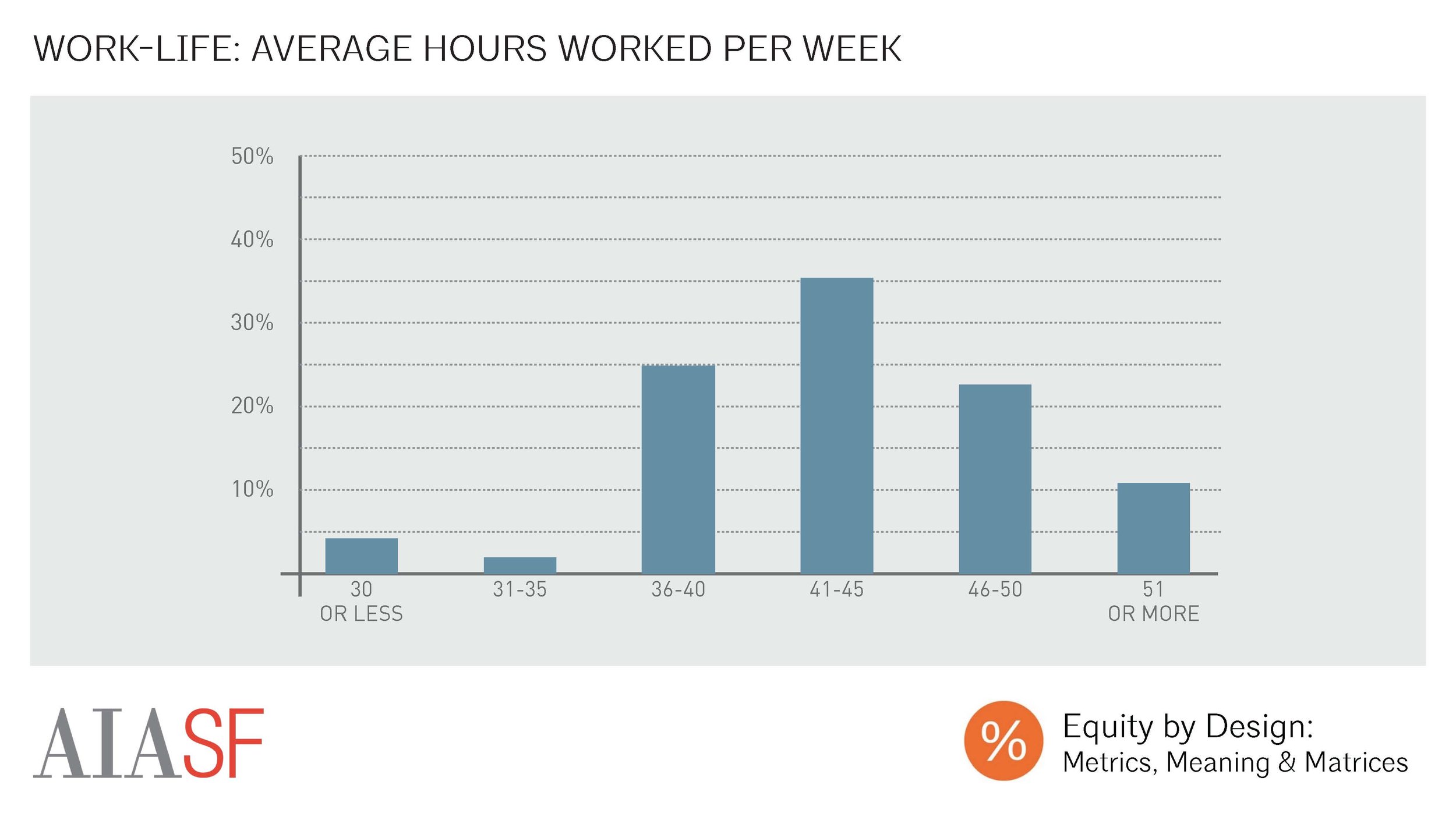

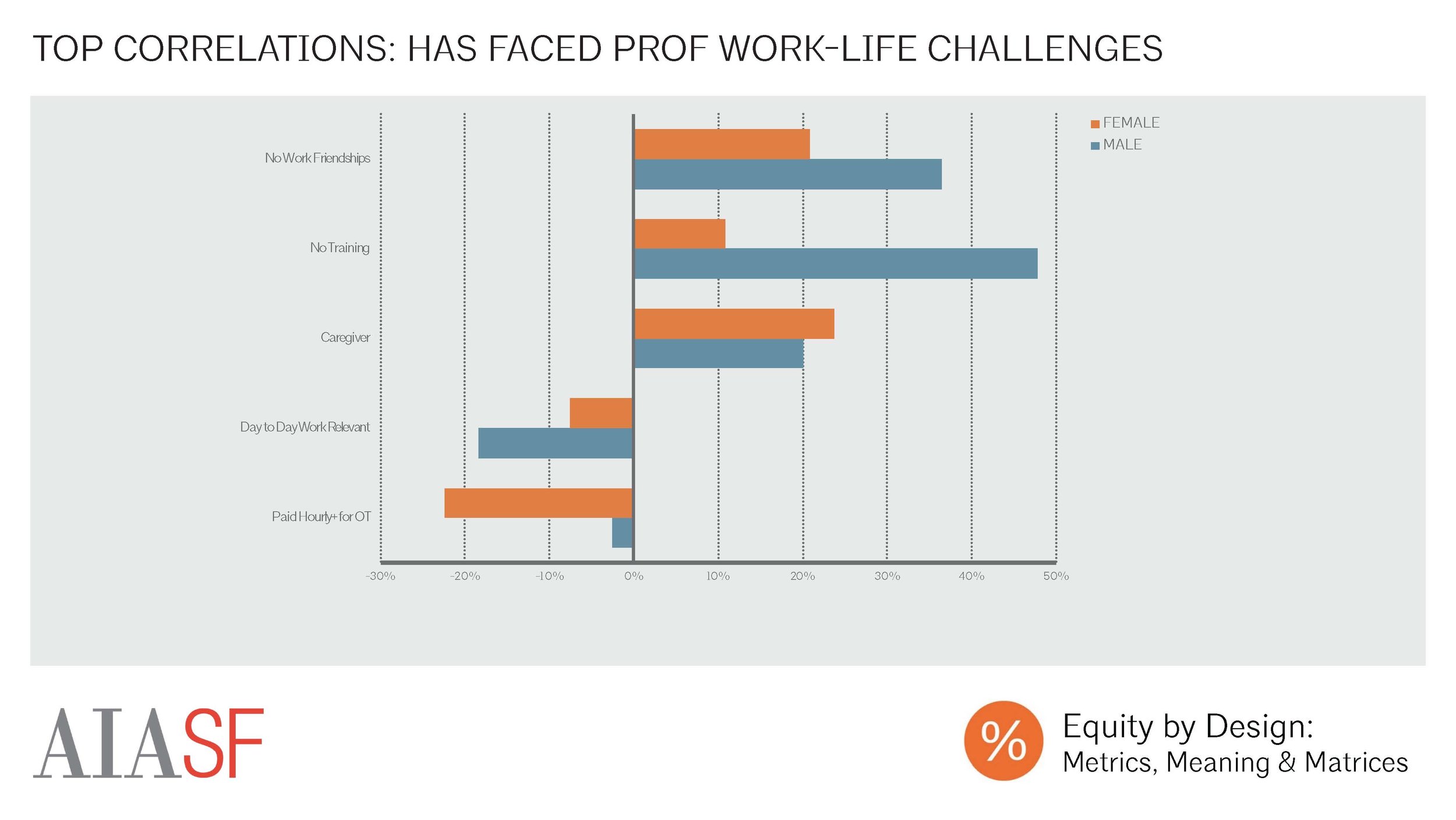

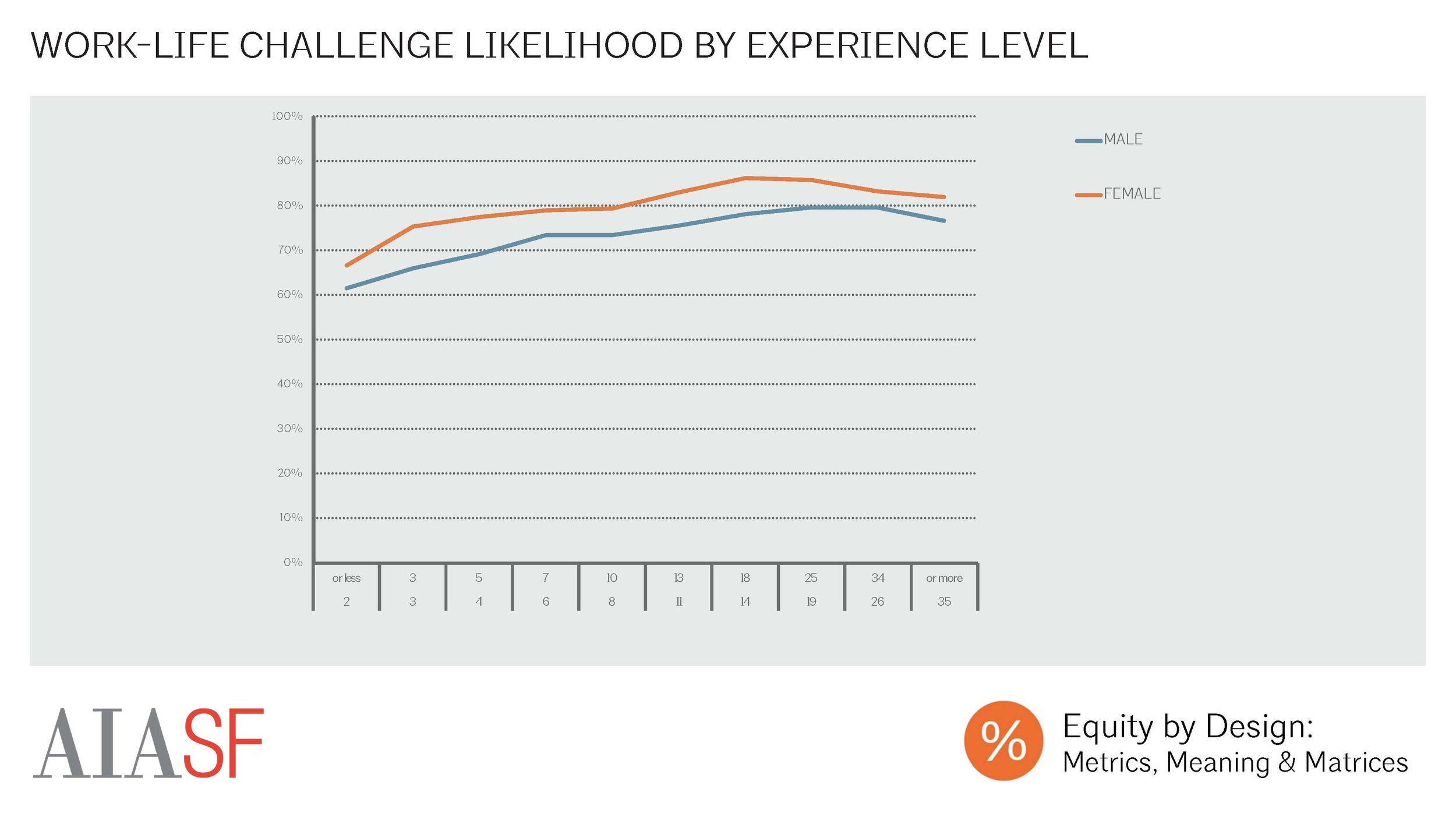

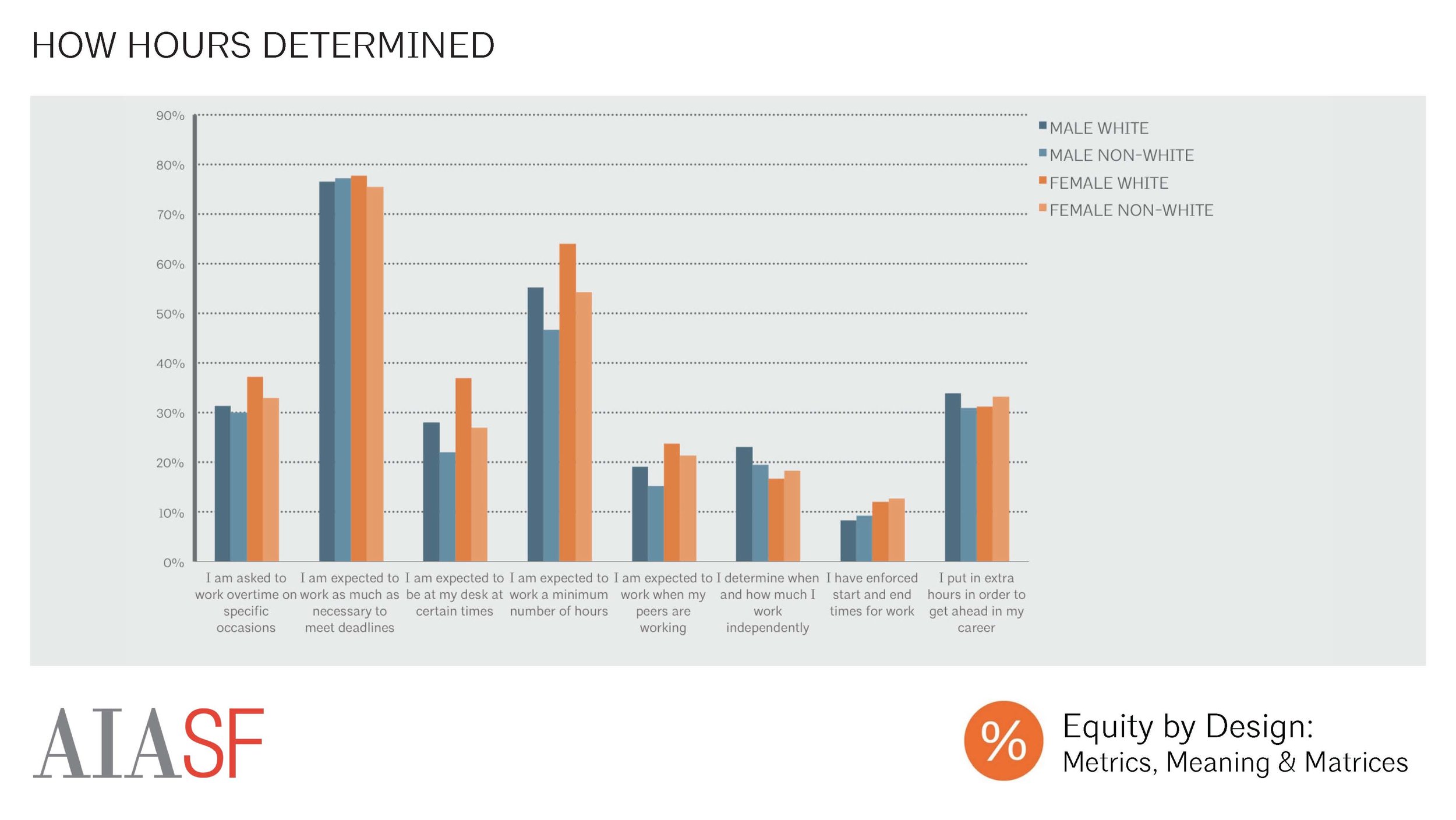

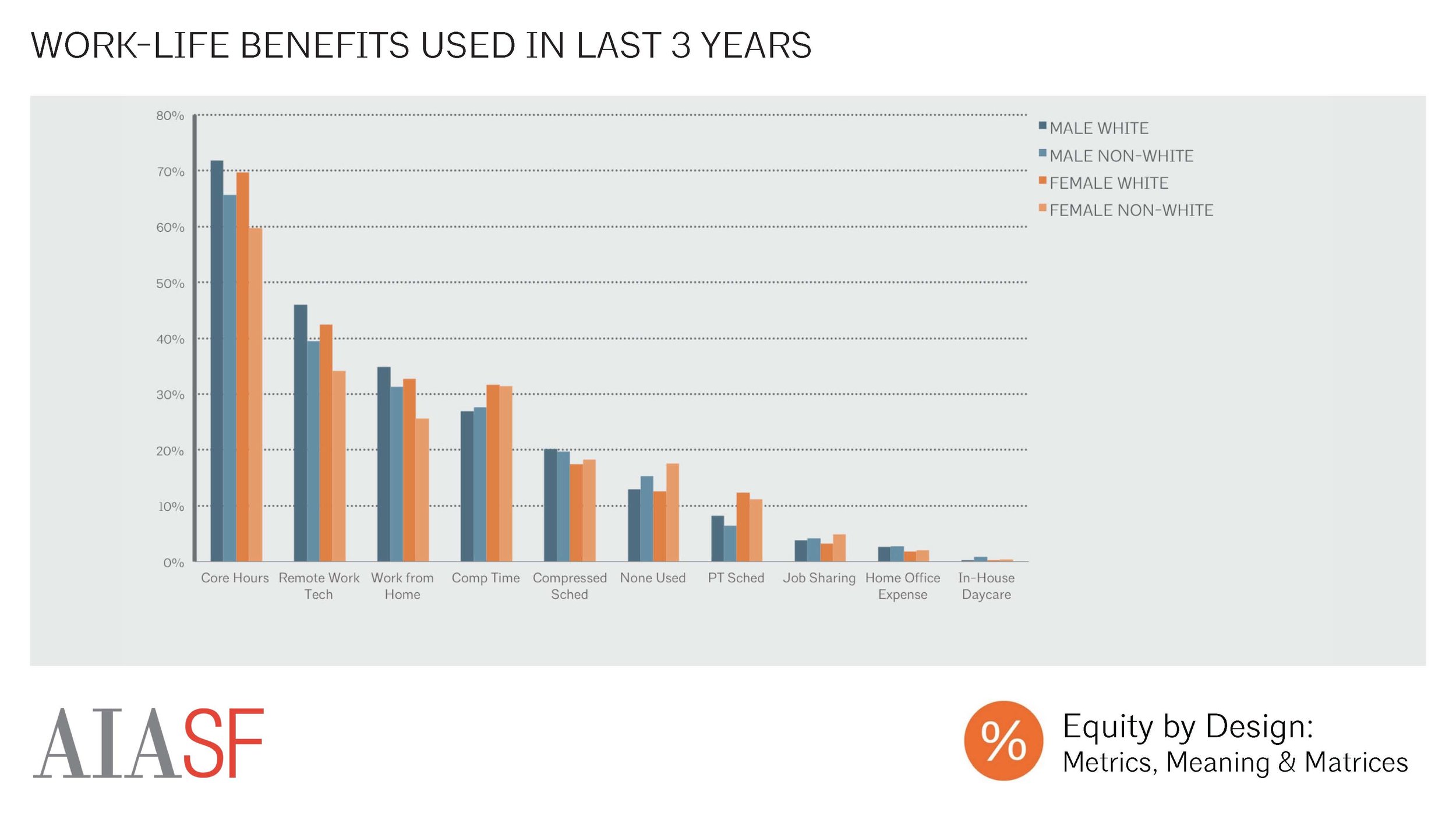

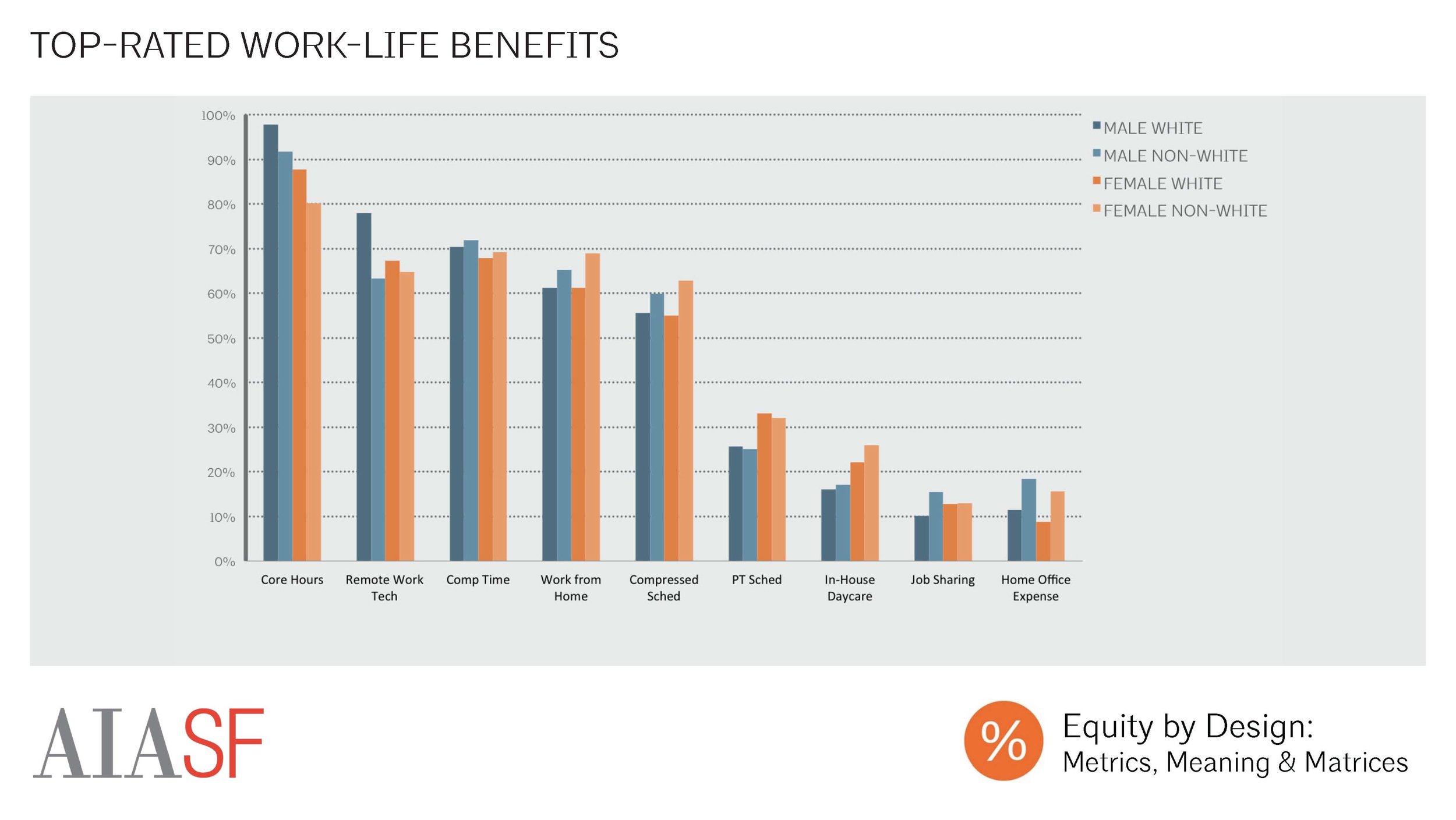

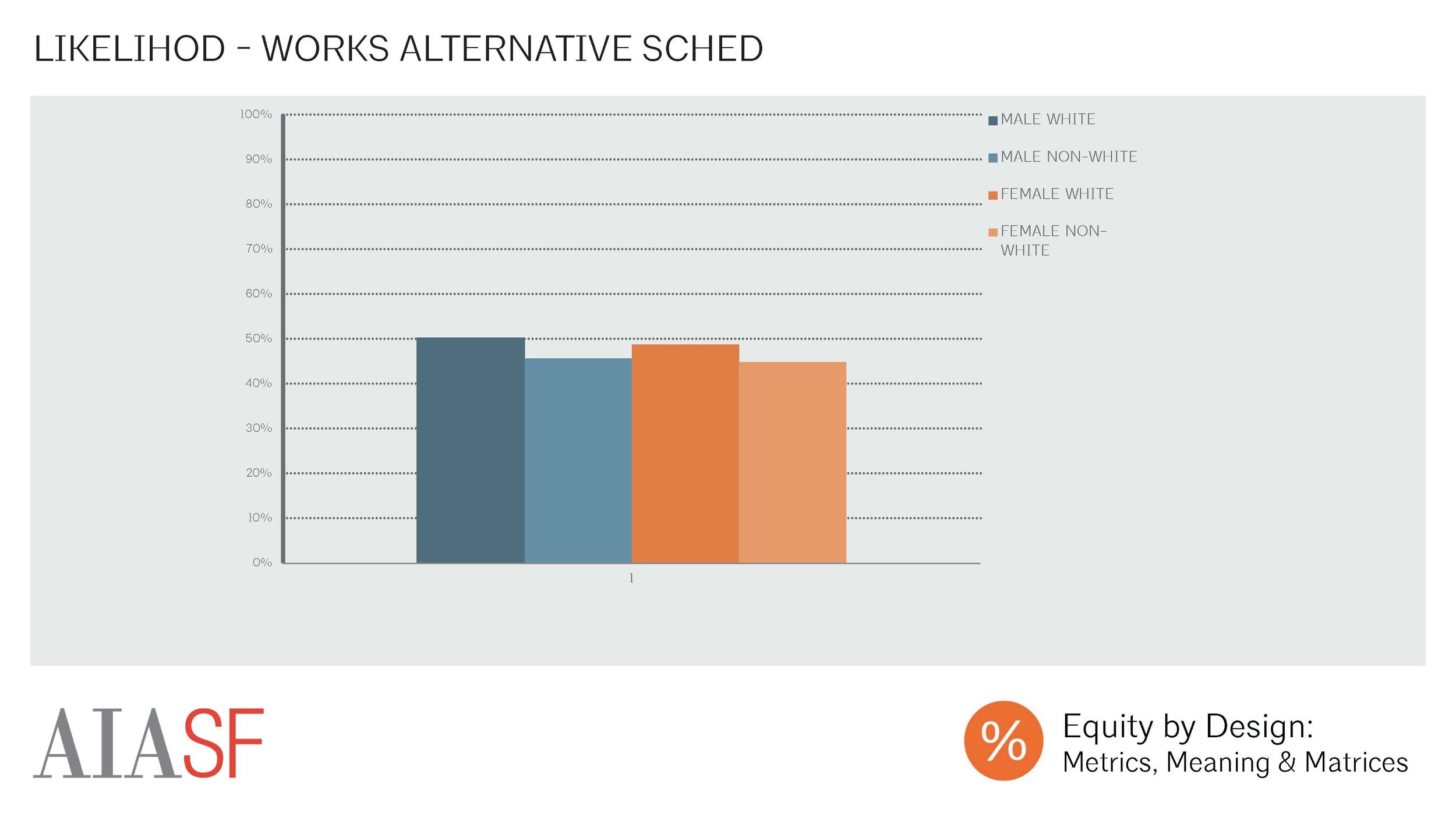

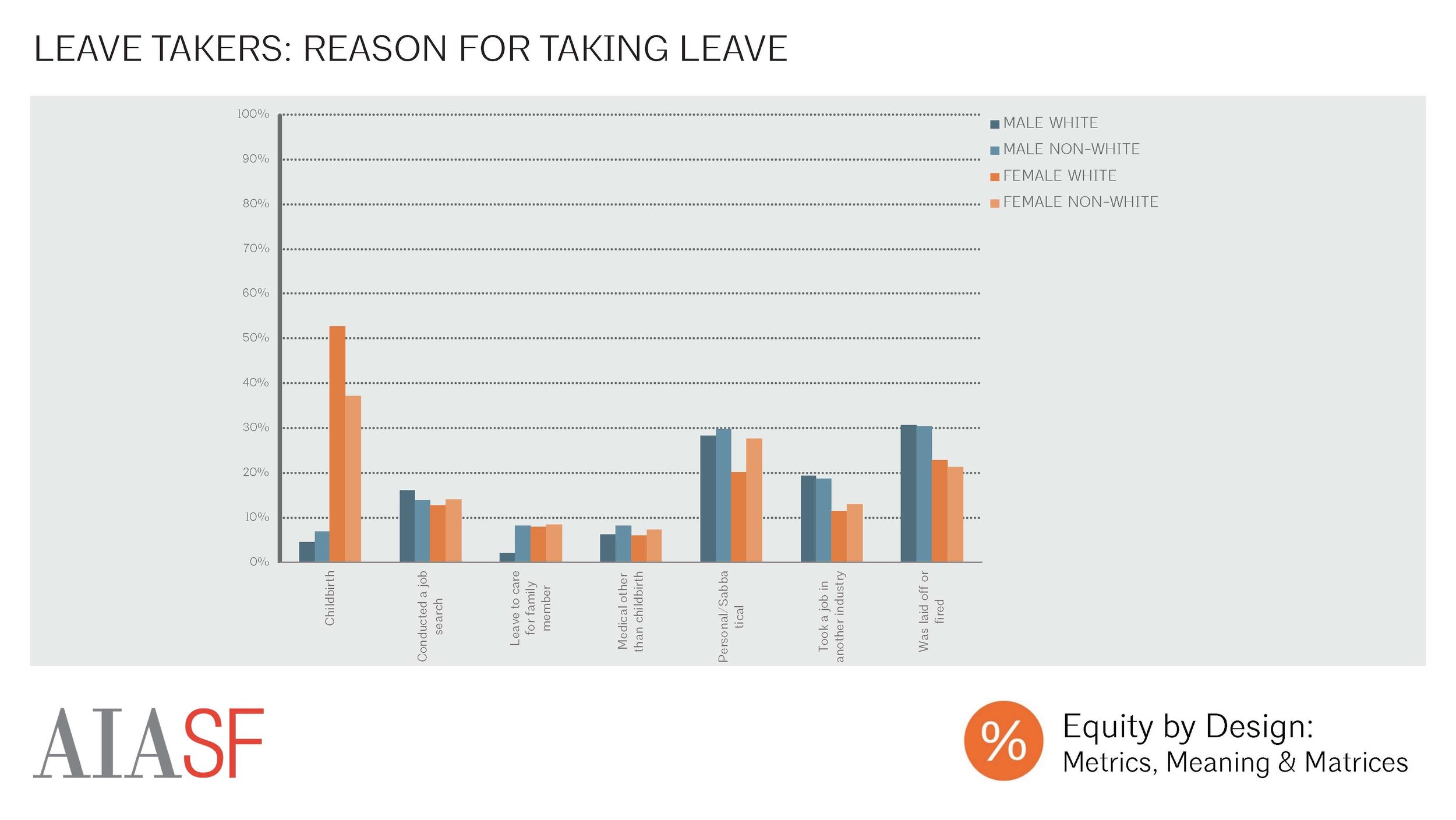

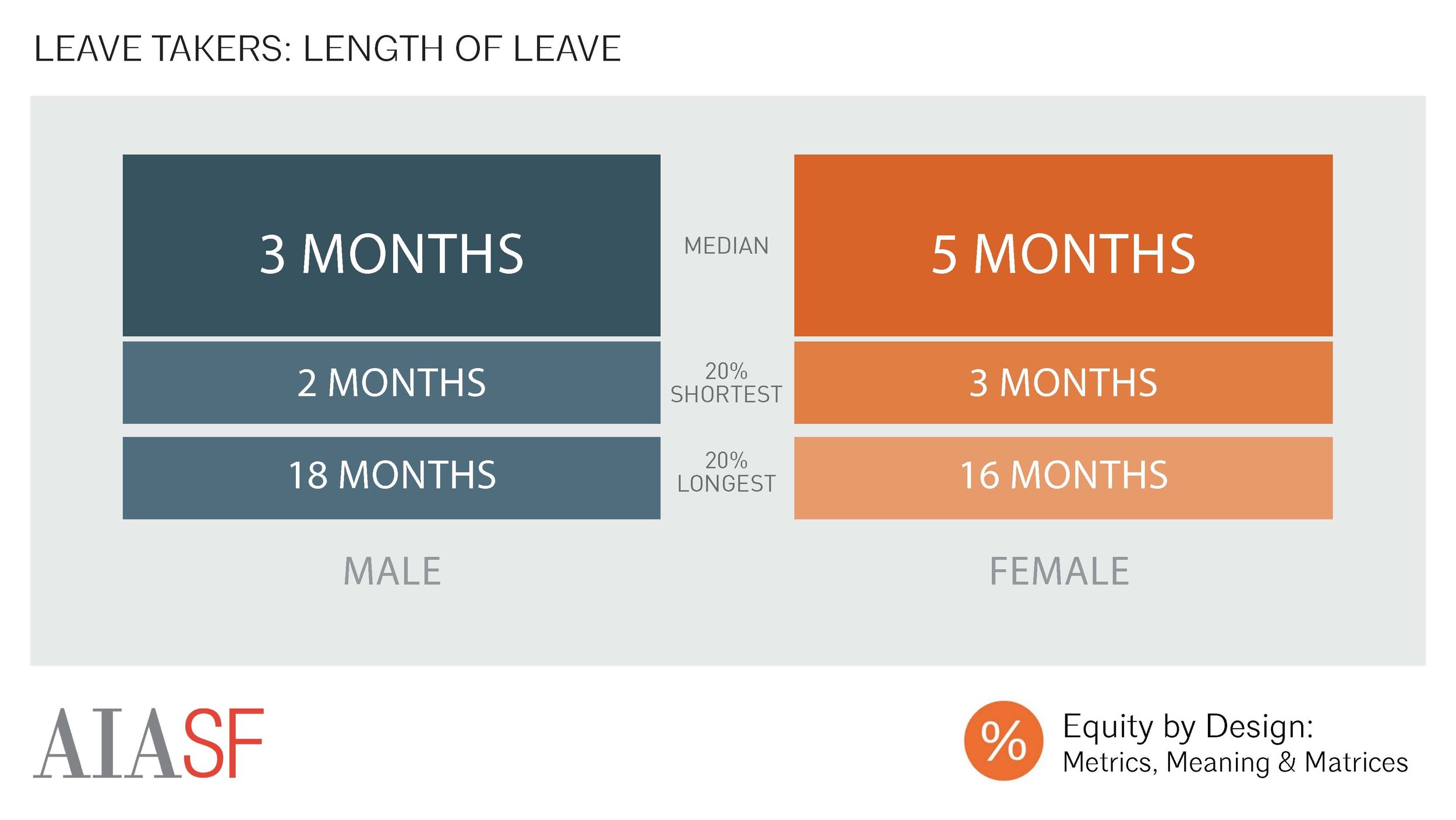

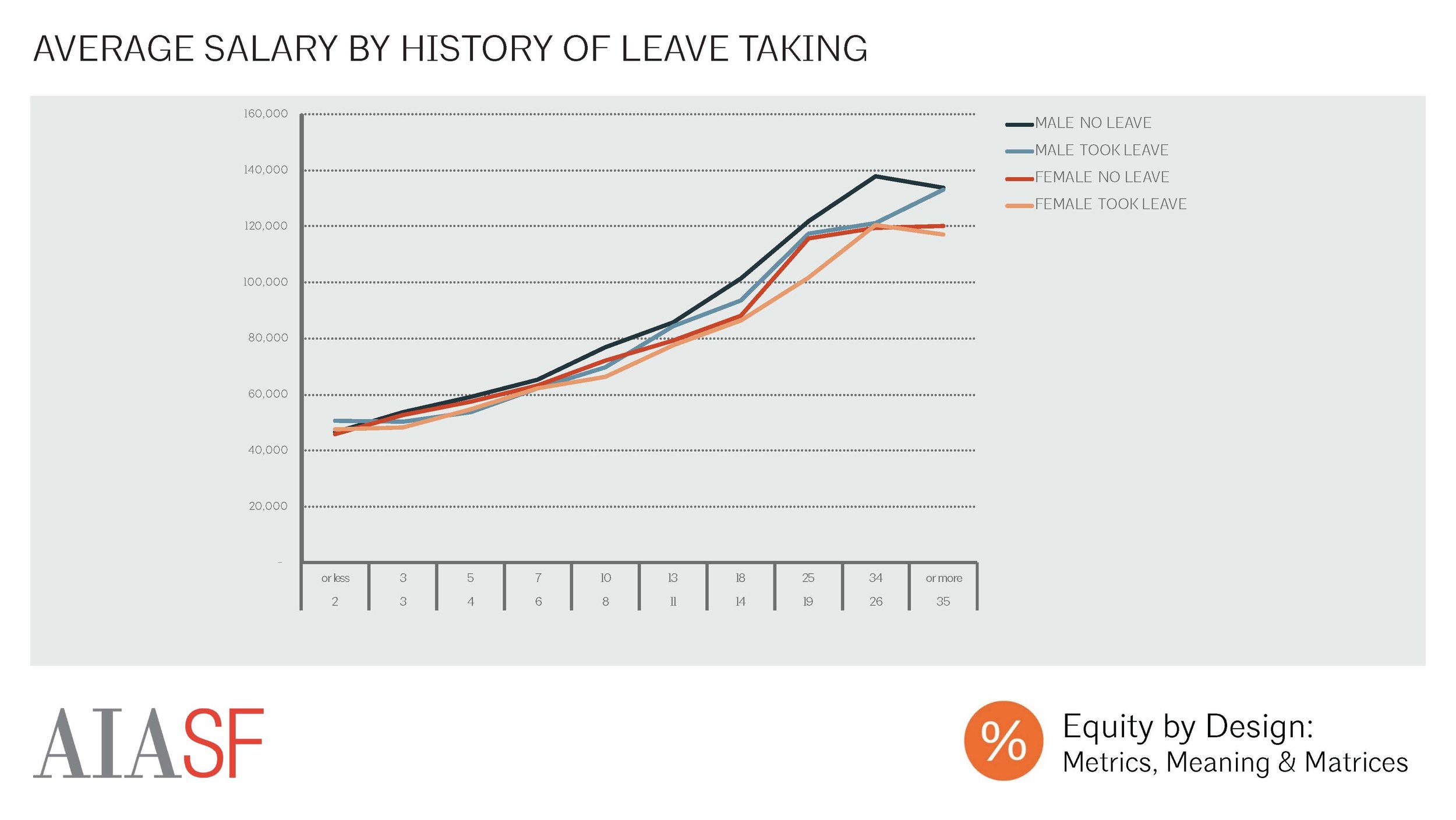

More significant to the pay gap in the US workforce are in-sector differences, which include differences in roles, responsibilities, and work environment within industries. These wage drivers, which account for the bulk of the wage gap in the US, will be the focus of today's article. The largest contributor to in-sector differences is what Goldin calls “temporal flexibility.” Women are more likely than men to take jobs that provide reduced hours, flexibility in hours, or work-life benefits like the ability to work from home or robust leave policies. These flexibility options, she has found, are associated with lower hourly earnings, indicating that women pay a price for access to flexibility.

Goldin’s work on the pay gap illustrates that the wage gap runs deeper than individual employers discriminating against individual workers when making compensation decisions (although this does happen!). Instead, the pay gap must be understood as a complex matrix of forces that produce gendered differences in workers’ choice of market sector, occupation, work setting and flexibility. In other words, simply saying that we must provide “equal pay for equal work” ignores the fact that gender is deeply entwined with the supposedly neutral criteria by which we value work in the first place.

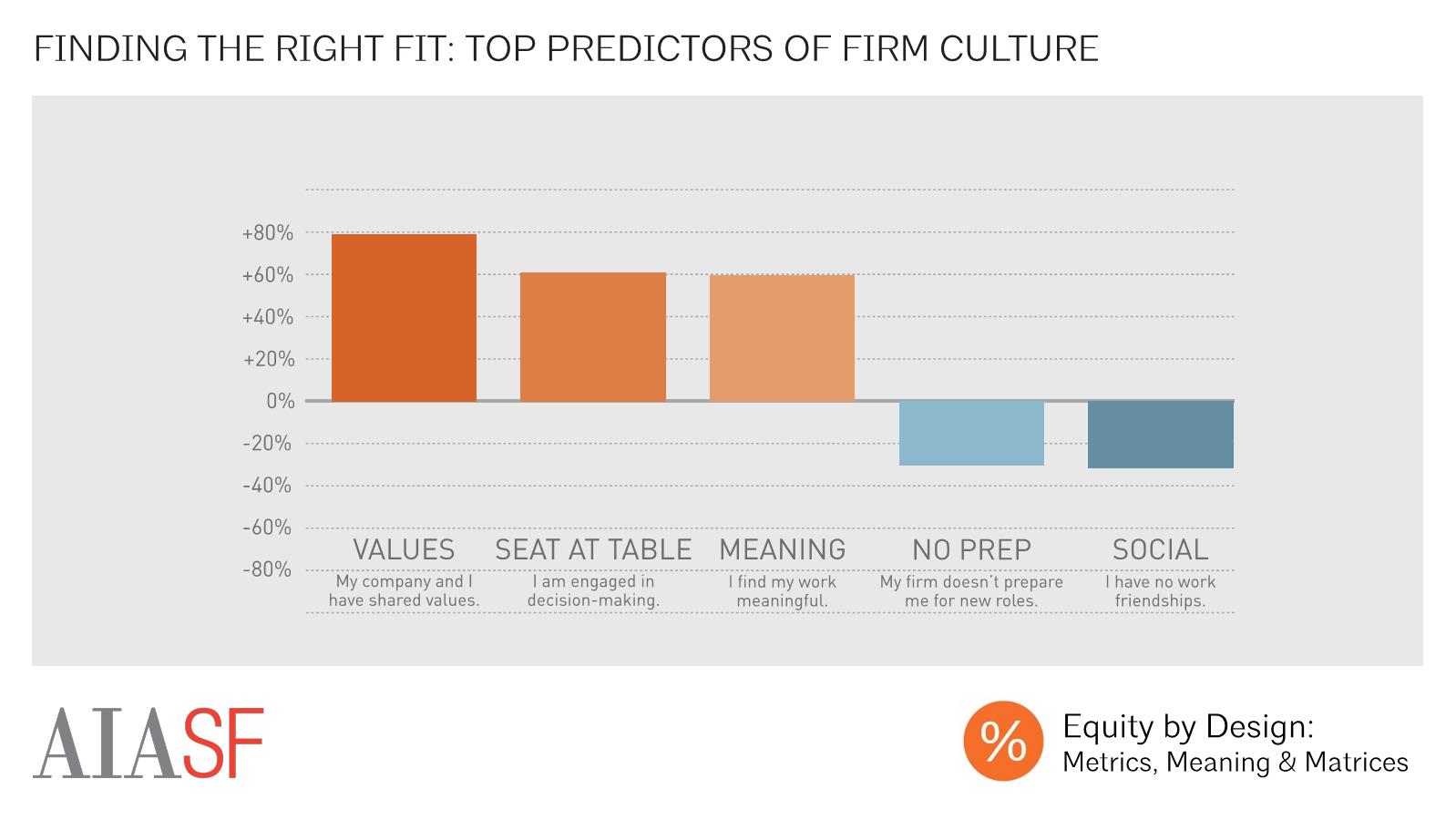

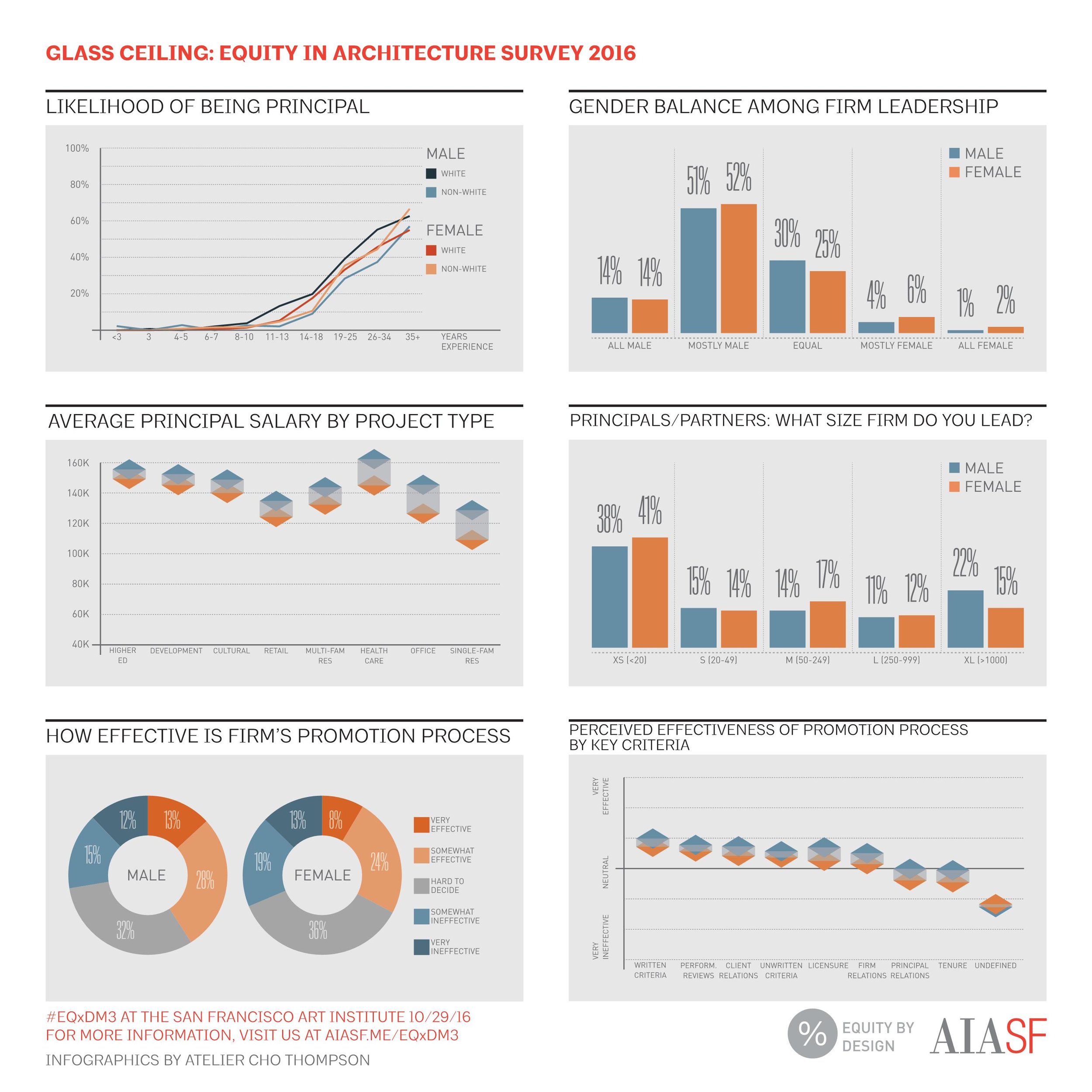

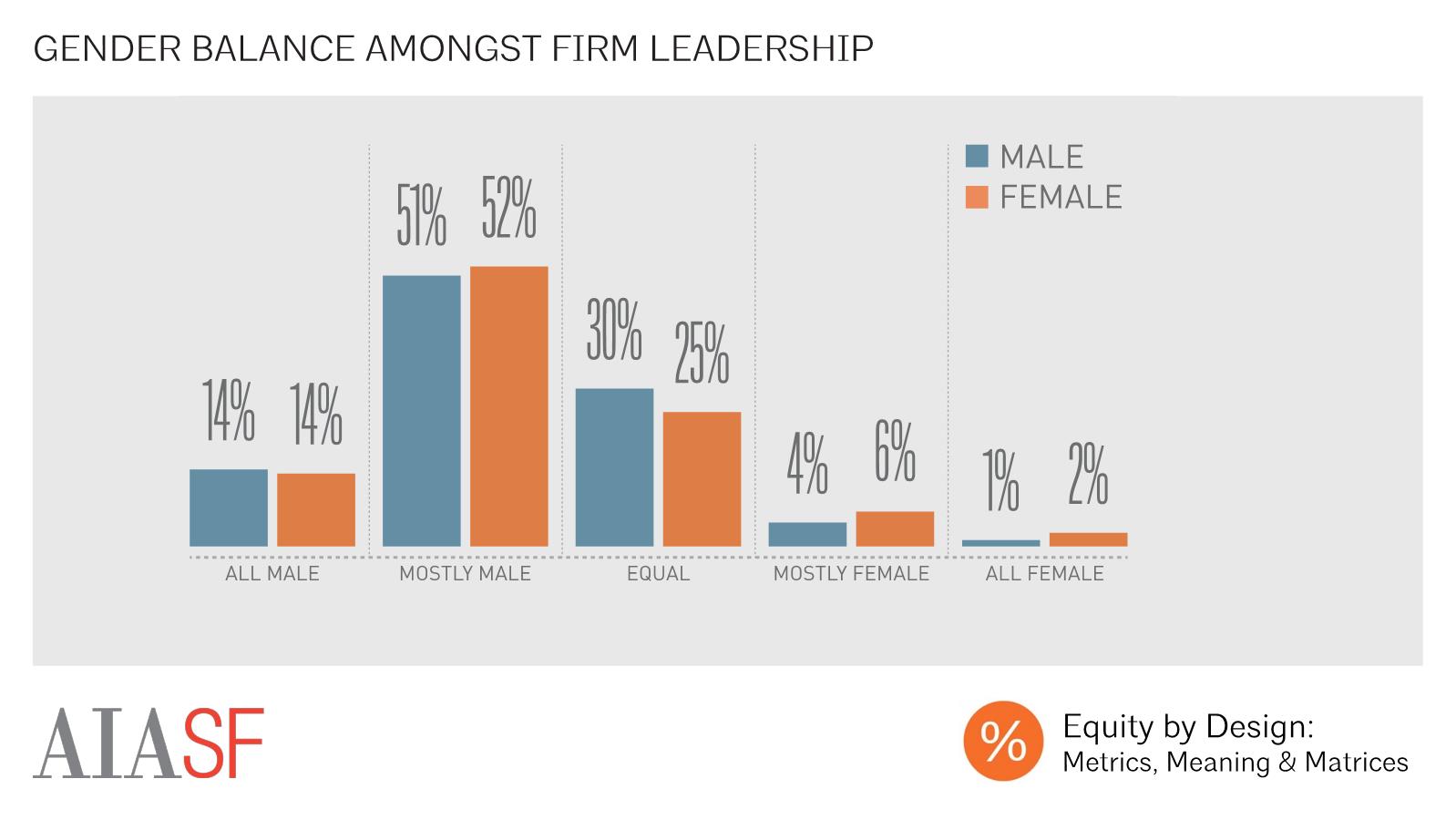

The 2016 Equity in Architecture Survey illustrates that these forces are at play within our industry:

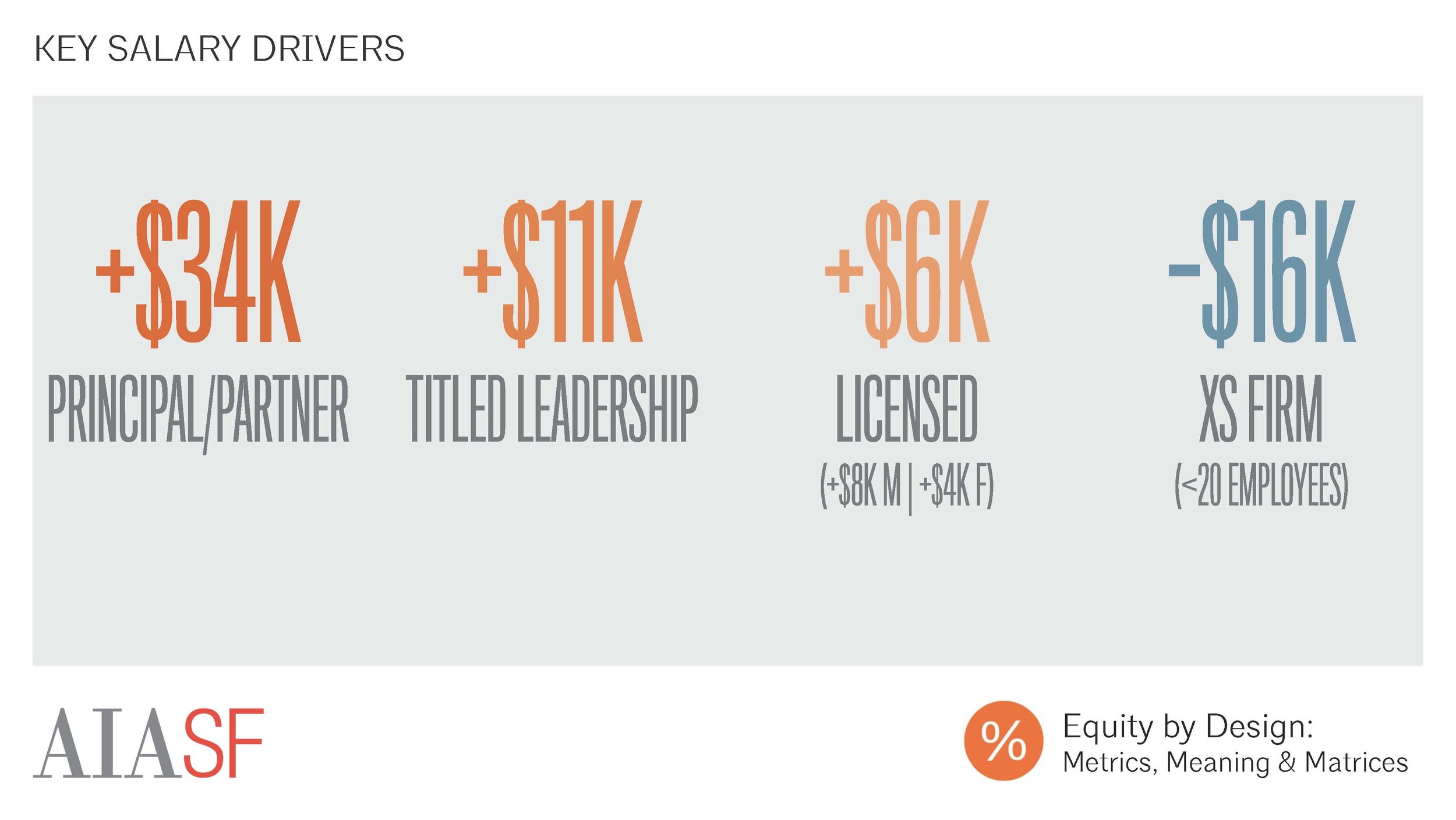

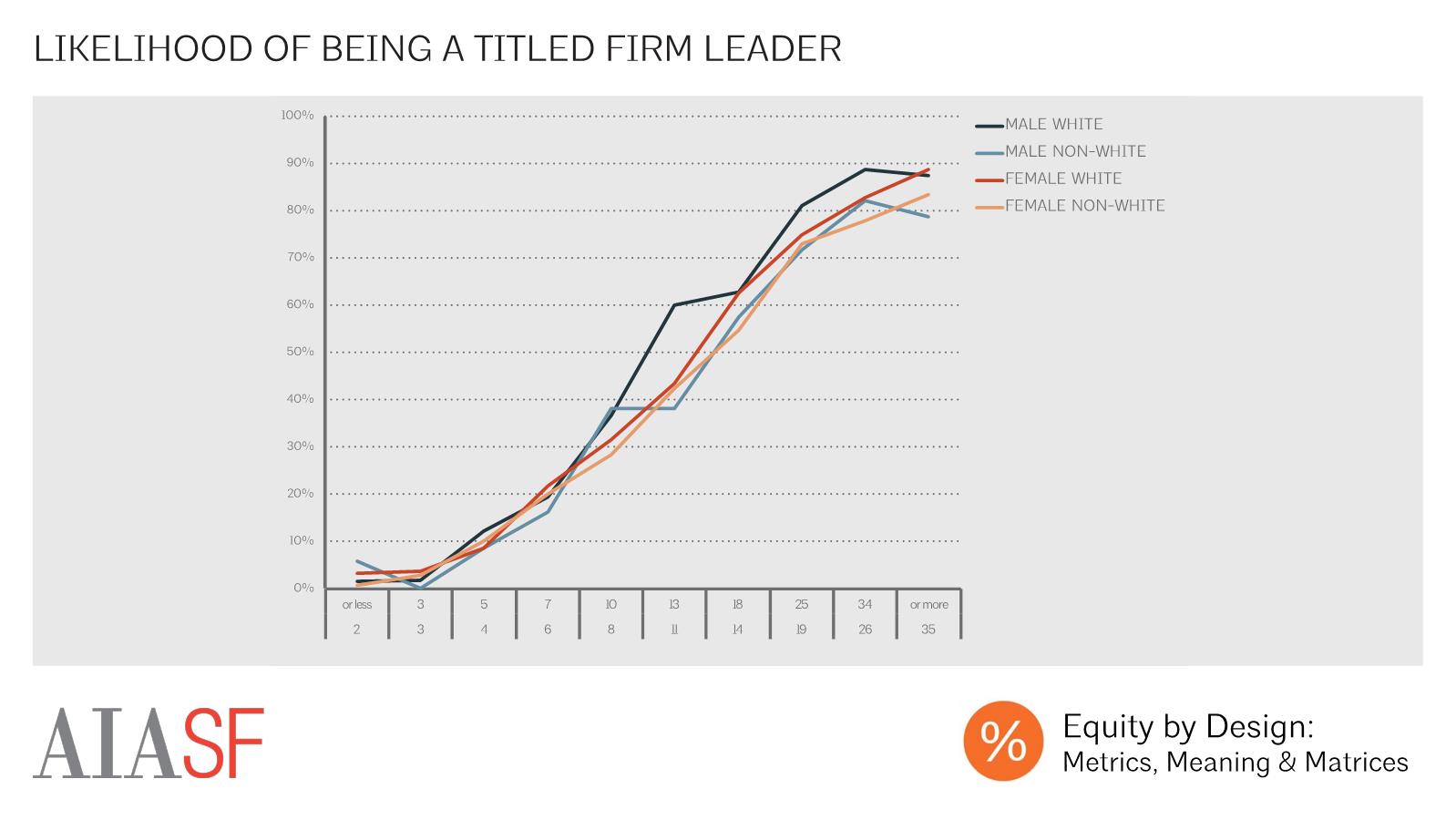

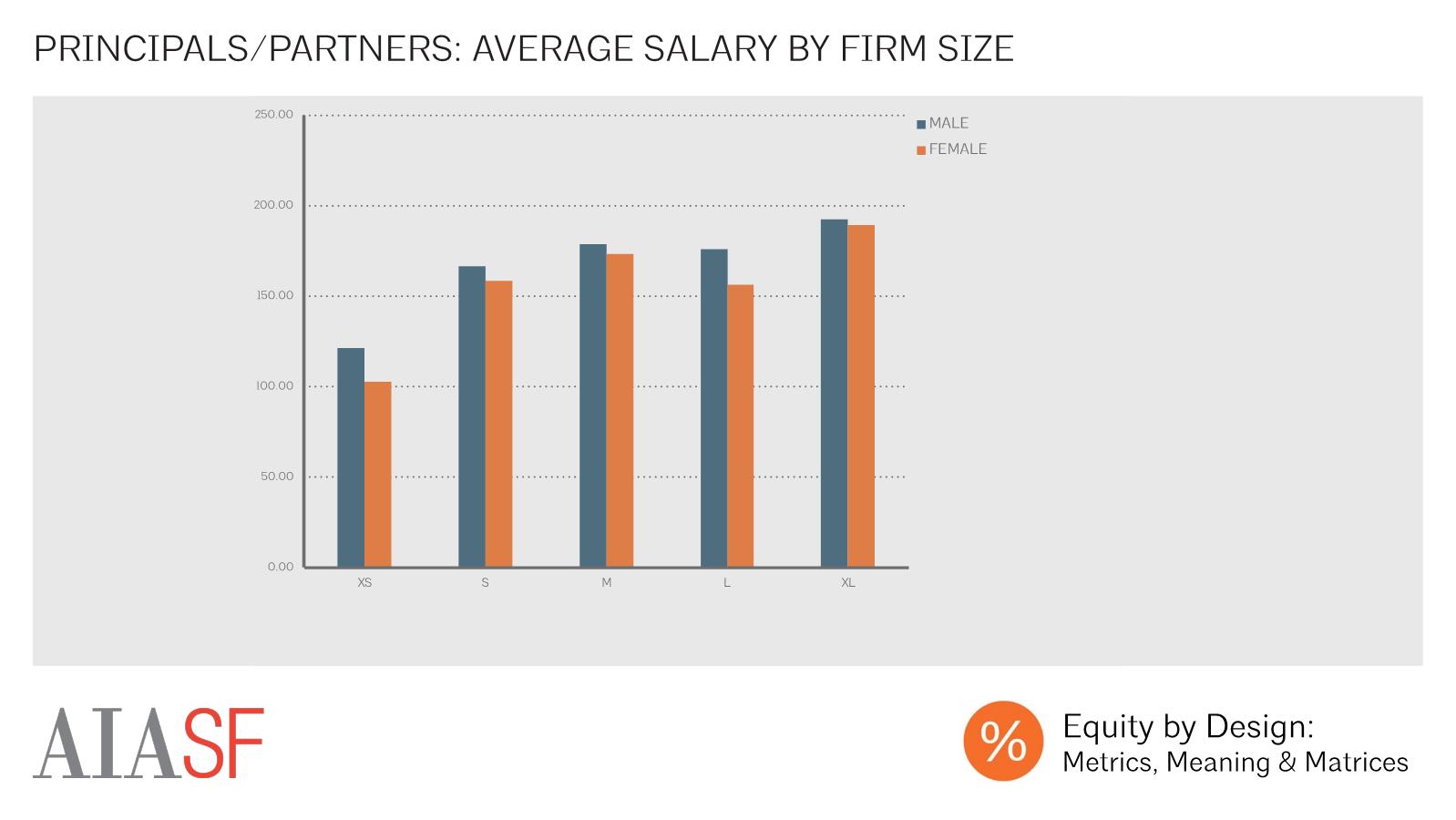

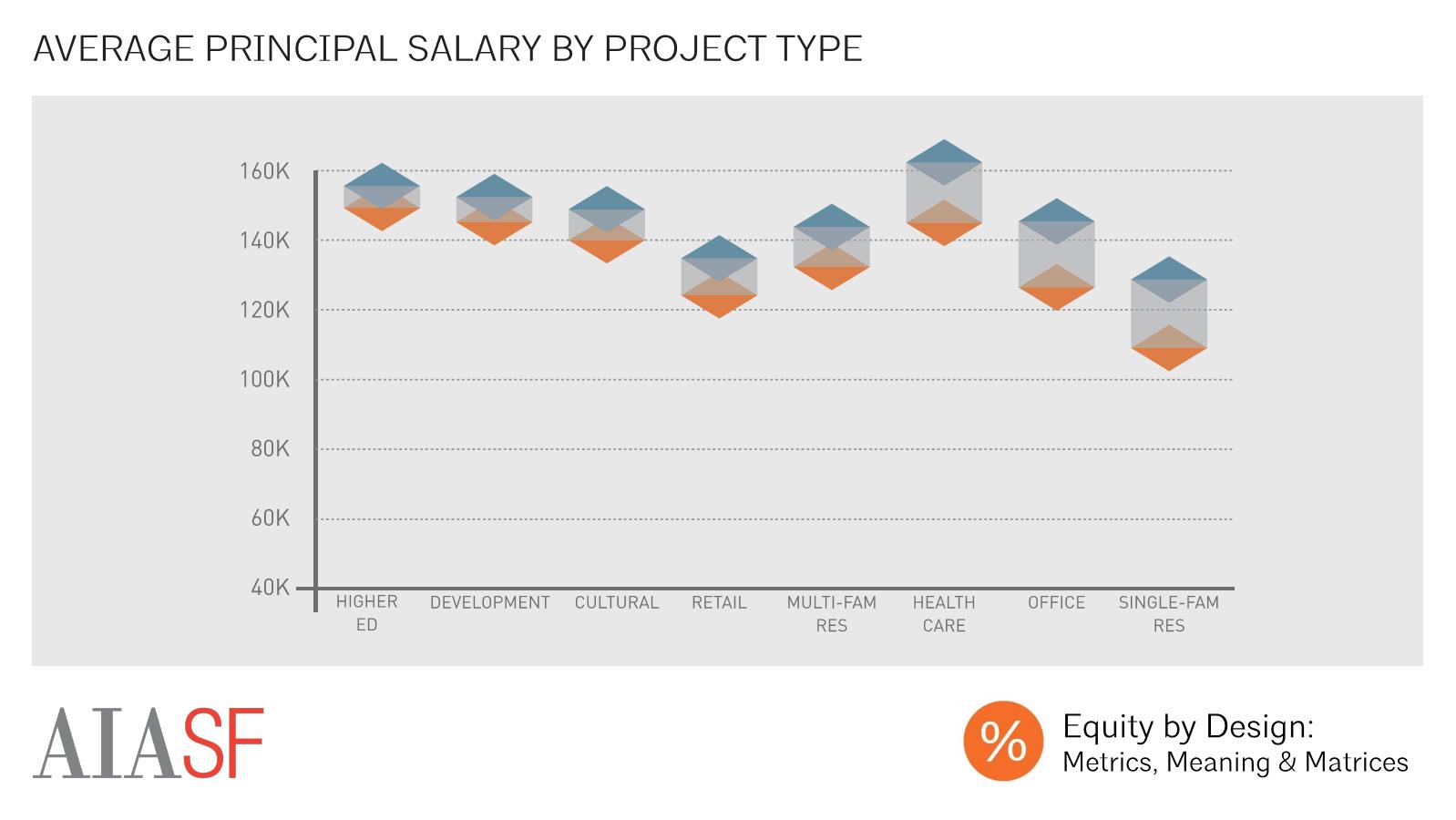

In many cases, there were significant wage advantages associated with choosing to work in particular settings – particularly within the largest firms, and within certain cities. These advantages were more significant for men than they were for women.

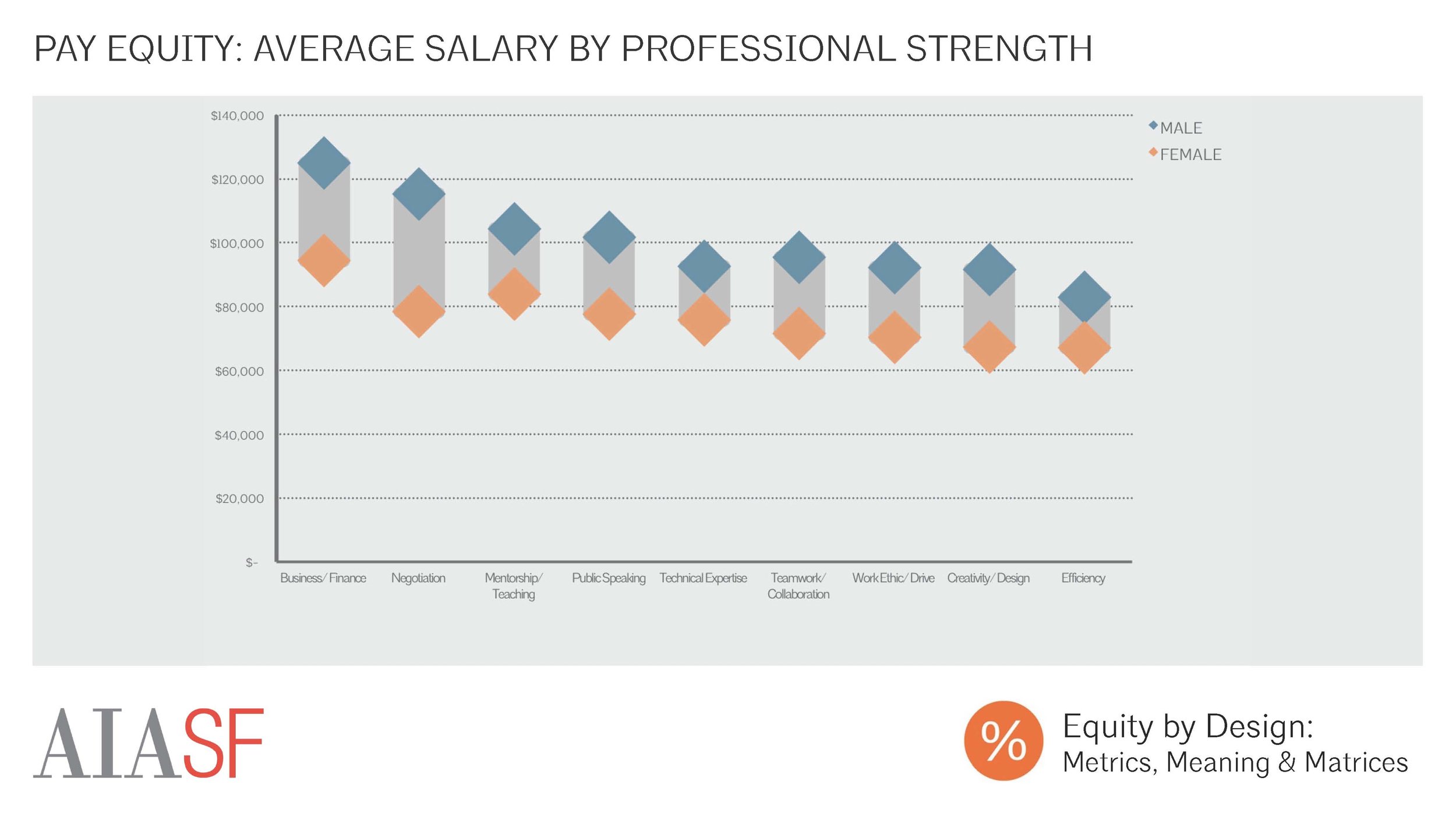

An individual’s schooling, professional history, strengths, and professional qualifications were also predictive of earnings. Again, many of the factors that were associated with the highest salaries overall were also associated with higher than average gender pay gaps

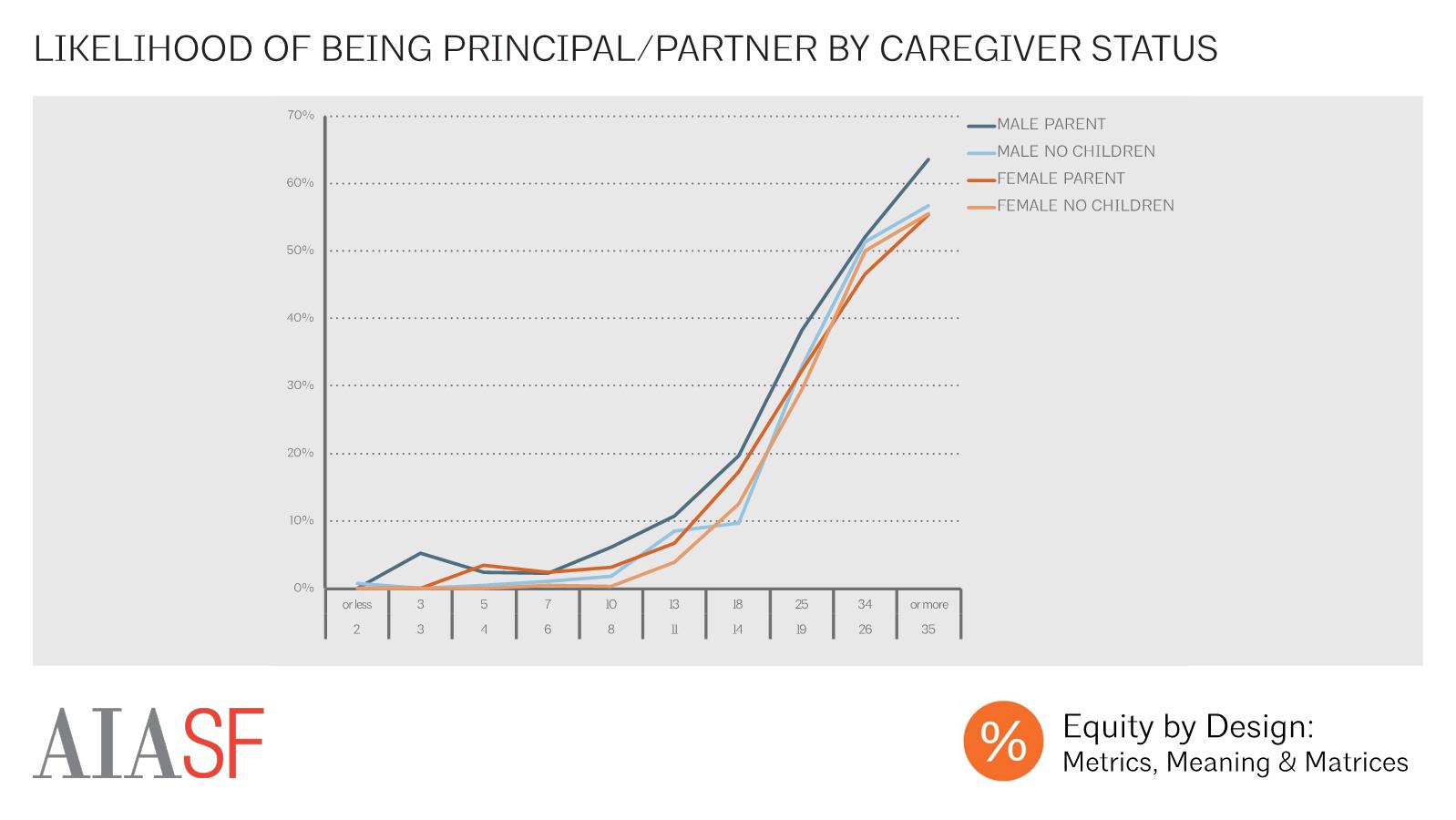

Temporal flexibility was identified as a major factor in pay inequality within the industry. Mothers made significantly less than fathers with comparable levels of experience, but also reported working less hours on average. Closing the wage gap amongst caregivers is likely to require more equal distribution of caregiving duties, as well as the implementation of policies and procedures whereby output and value provided to one’s firm are at least as important as billable hours in determining earnings.

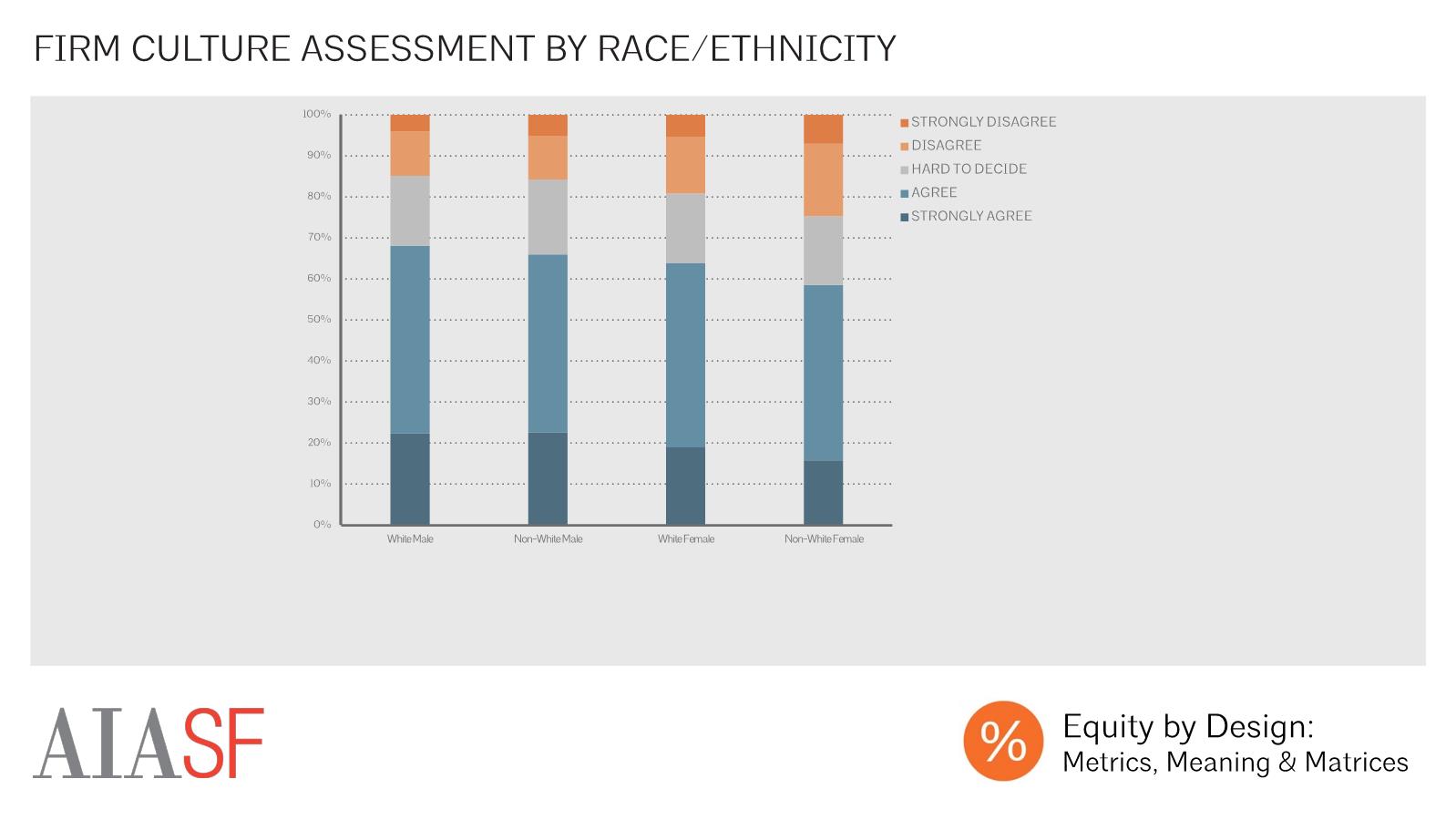

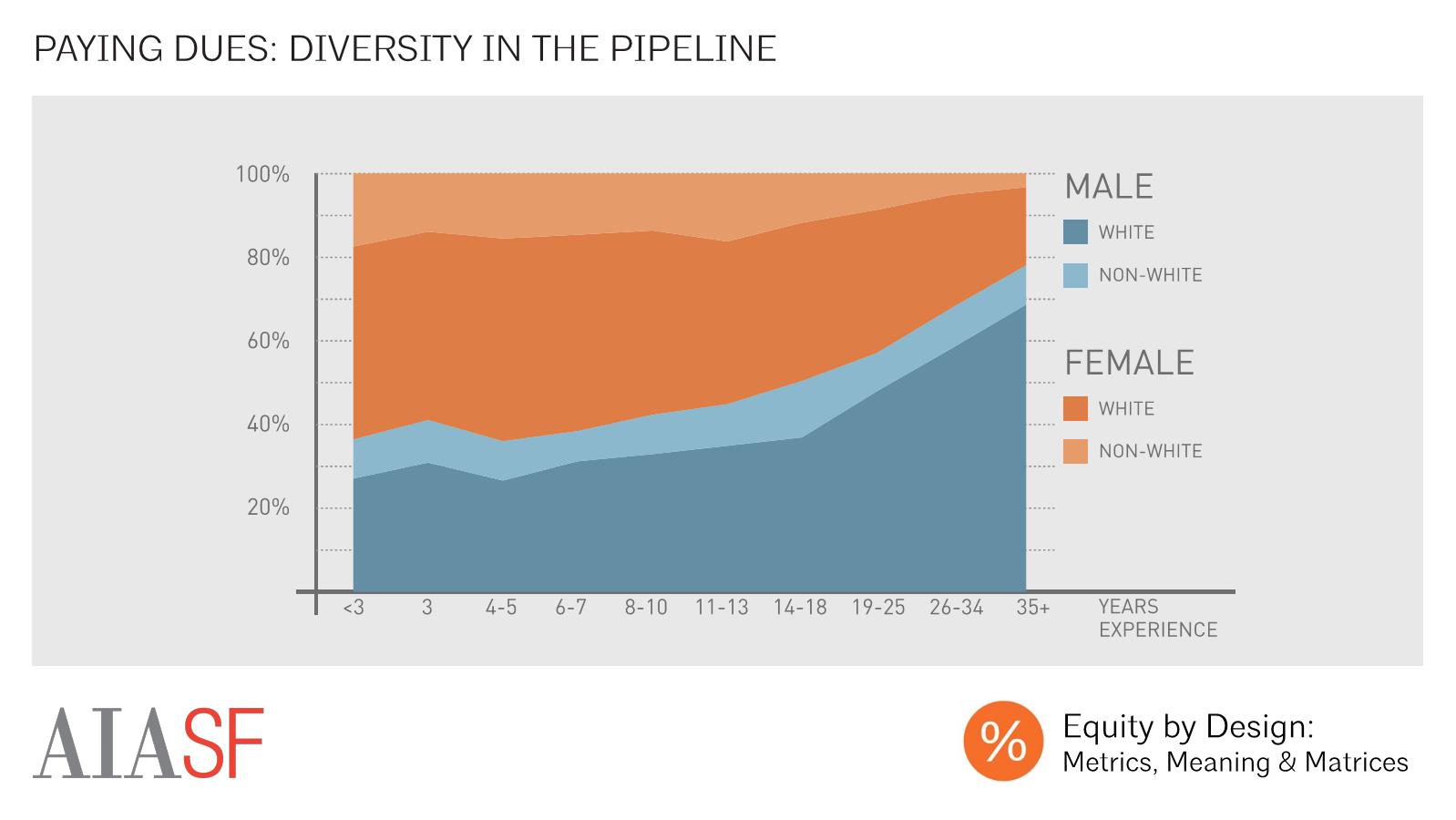

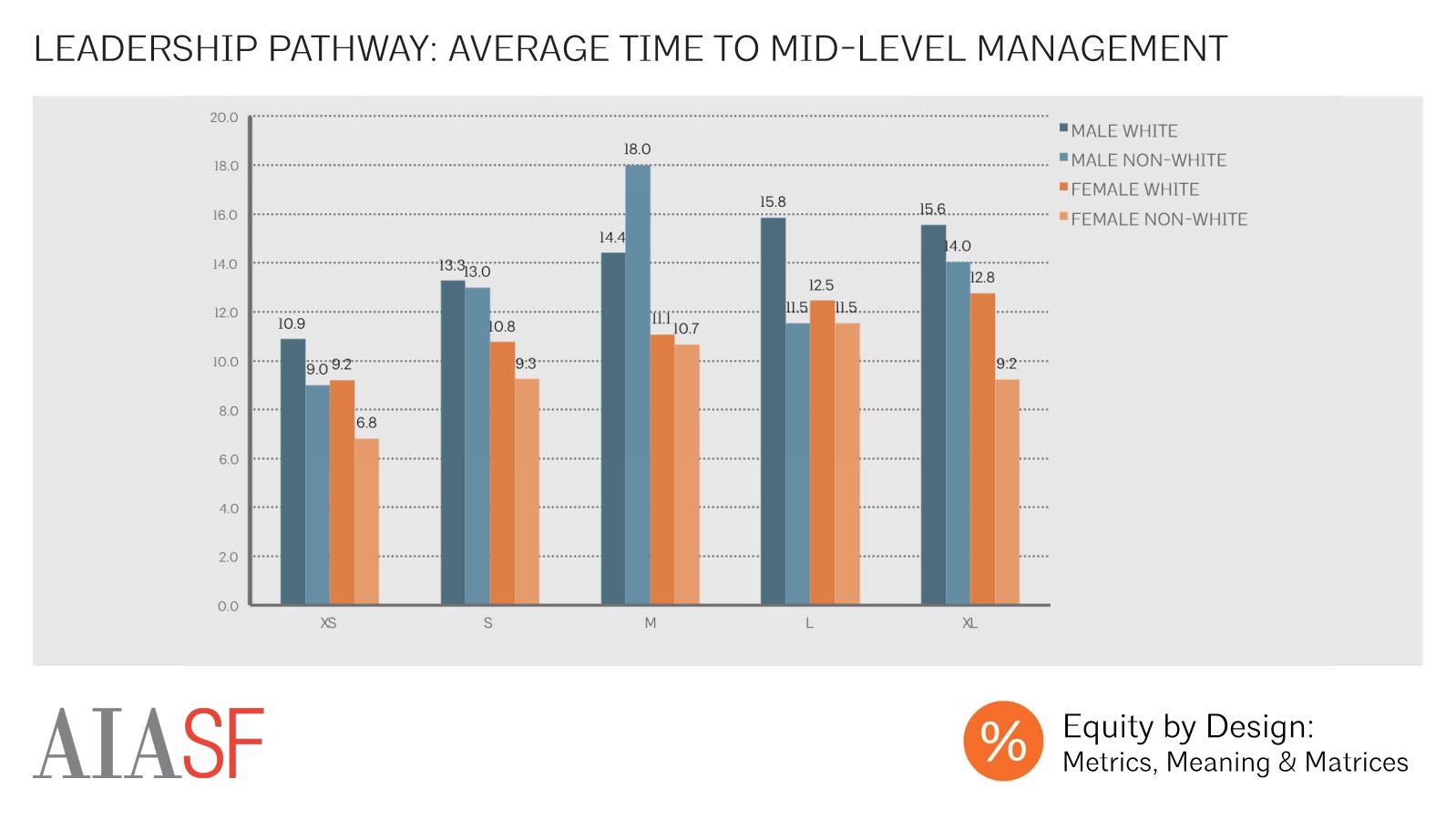

As we saw in our last article, there are also significant differences in pay on the basis of race and ethnicity, with black or African American respondents earning less than other respondents at nearly every point in their careers. Because this group is underrepresented in the field, and in our survey sample, it wasn’t possible to perform the cross tabulations that you’ll see in today’s article on the basis of individual racial or ethnic group. We hope to oversample this population in our next round of research so that we can obtain statistically significant results from the more detailed types of analysis that the 2016 sample allows us to do on the basis of gender. Our hope is that this will allow the AEC community to better understand the dynamics that are driving the race and ethnicity-based pay gap and other important issues.

Key Salary Predictors

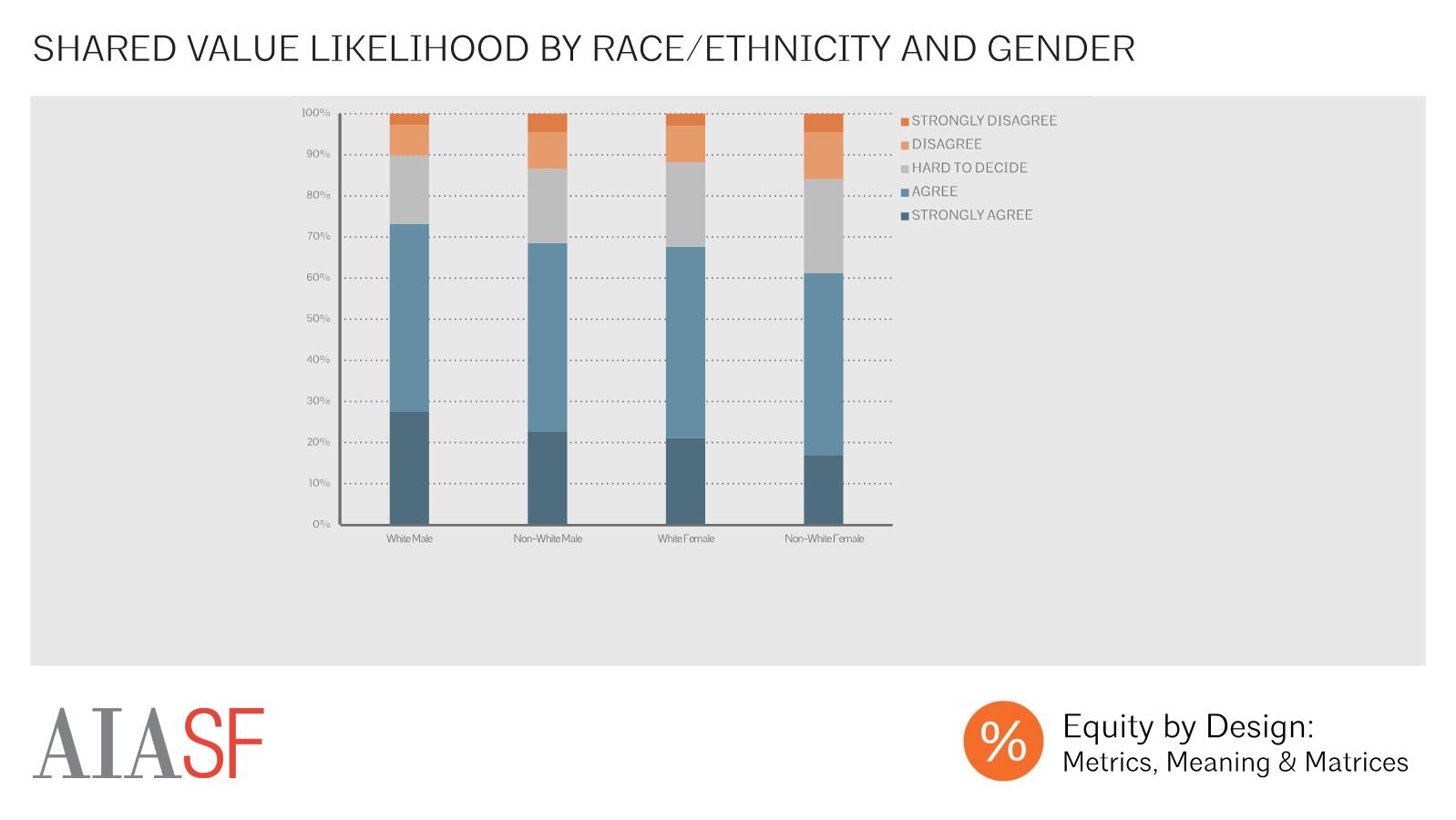

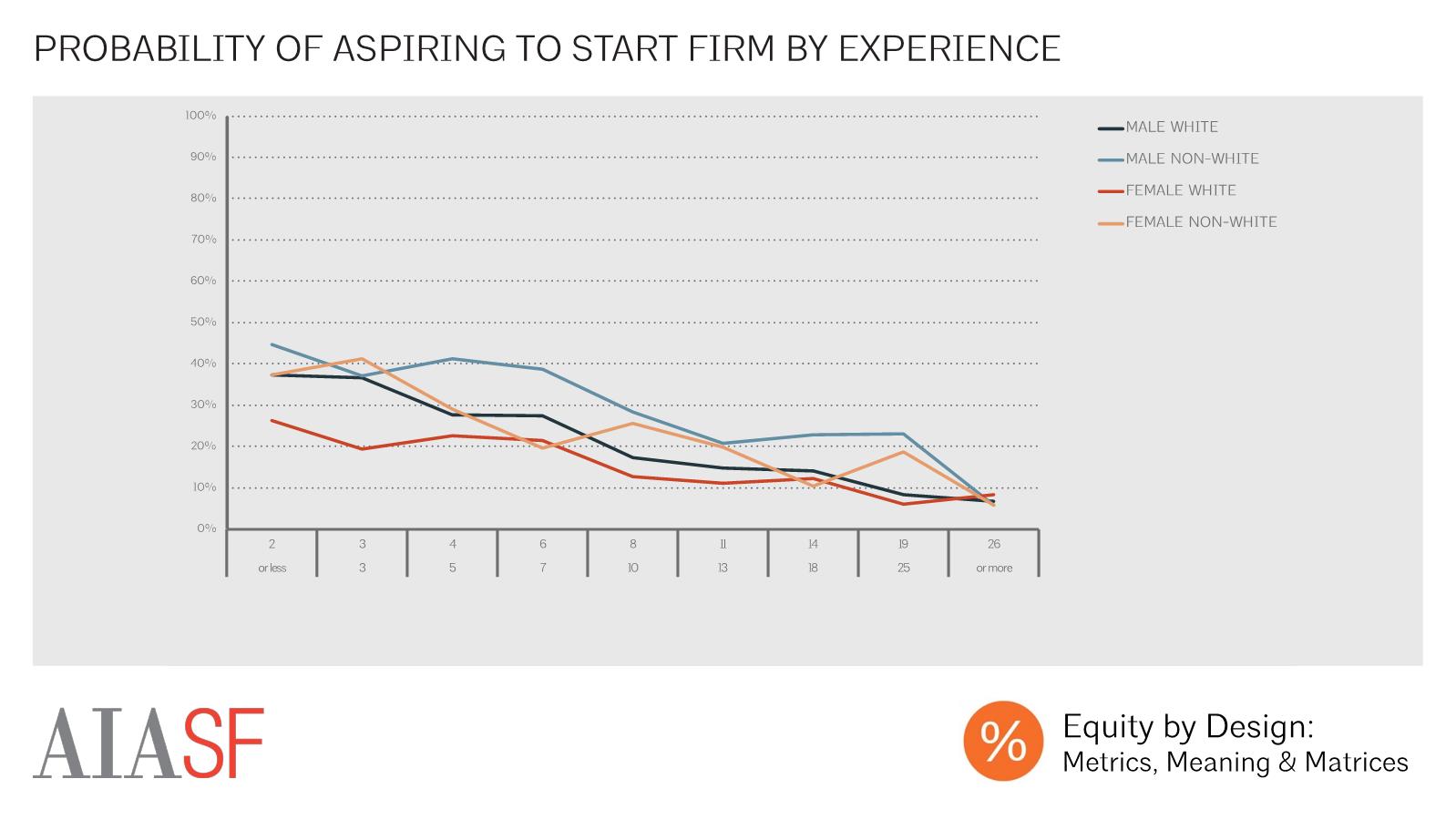

White male respondents made more annually, on average, than white women or people of color. While white men made $96,514, on average, non-white women earned $69,550 on average. It’s important to note, however, that a large part of this difference in annual earnings can be attributed to discrepancies in the average experience level of demographic groups within the survey sample – while the average white male respondent had 18.5 years of experience, the average non-white female averaged 9.0 years, for instance.