In 1978, Marilyn Loden was the final panelist to present in a session on “messages of limitation which confront women and the effect on aspirations.” In turn, each of the panelists described women’s failures to get ahead -- women didn’t have high enough self-esteem, or were inadequately socialized for leadership roles. Women, in short, were to blame for their collective lack of professional advancement. When it was Loden’s turn to speak, she chose to describe invisible, and yet systemic, barriers that hindered women’s career progression and, over time, created a climate in which they were less likely to aspire to attain the leadership positions that felt far beyond their collective grasp. The term that she coined to describe this phenomenon was “glass ceiling.”

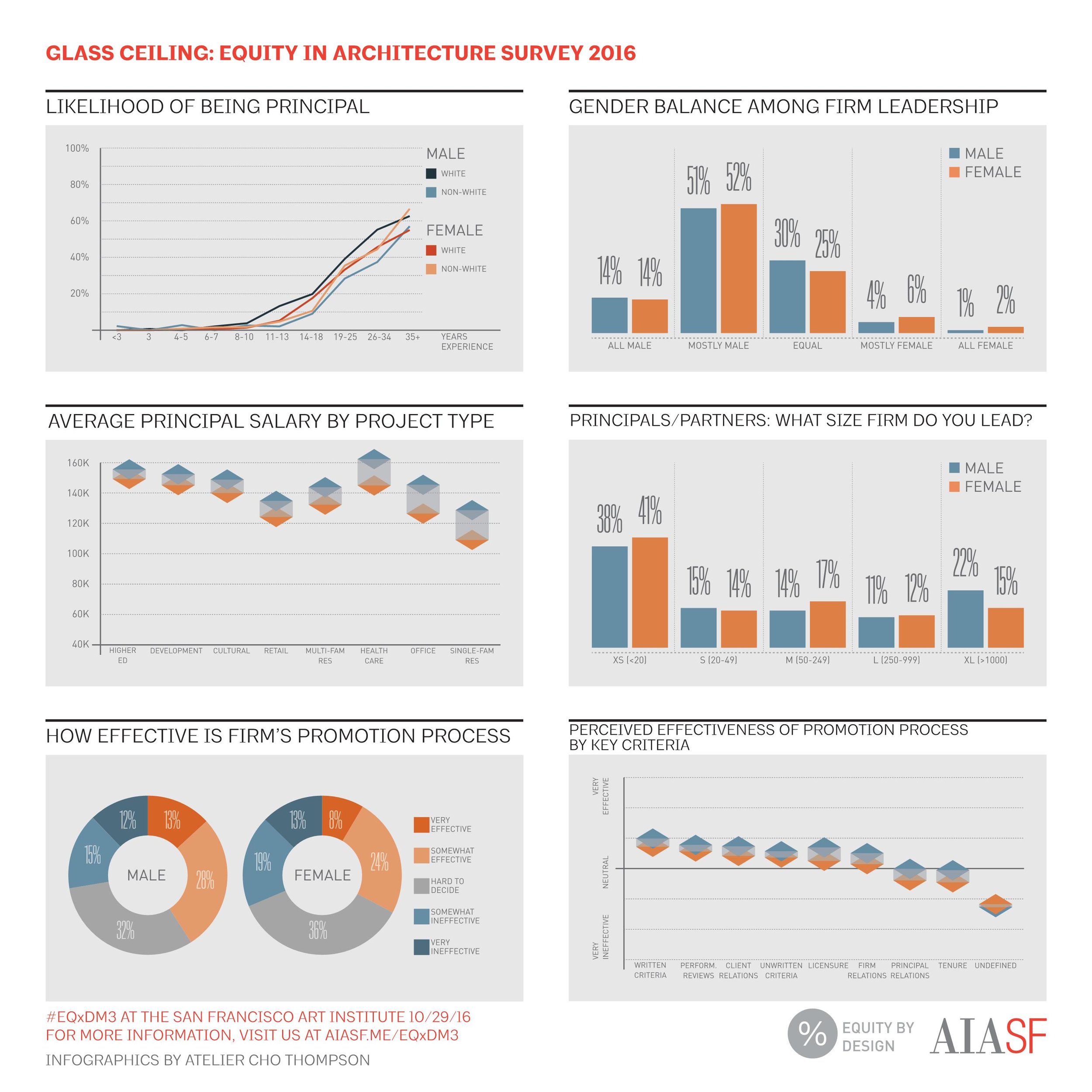

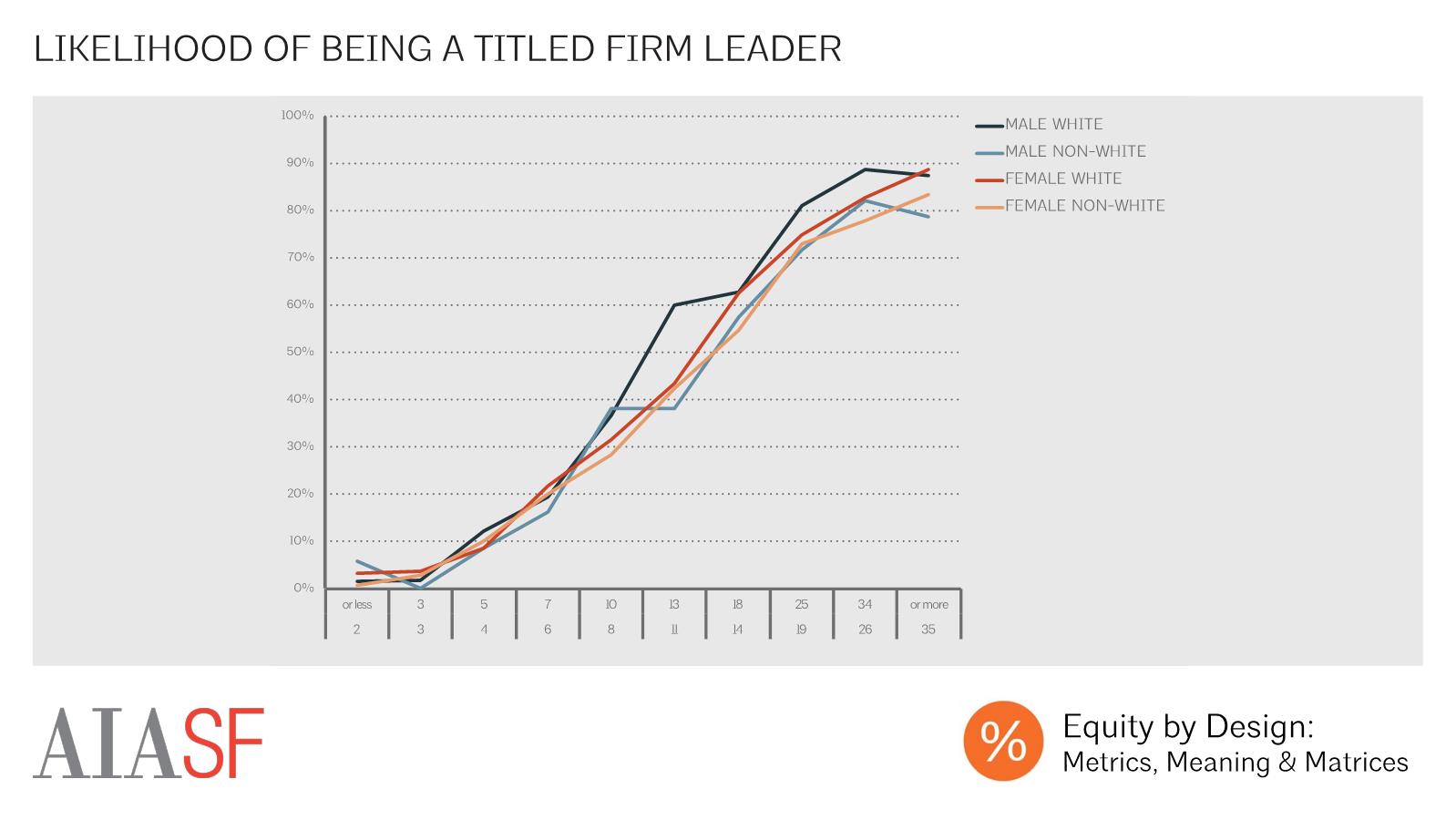

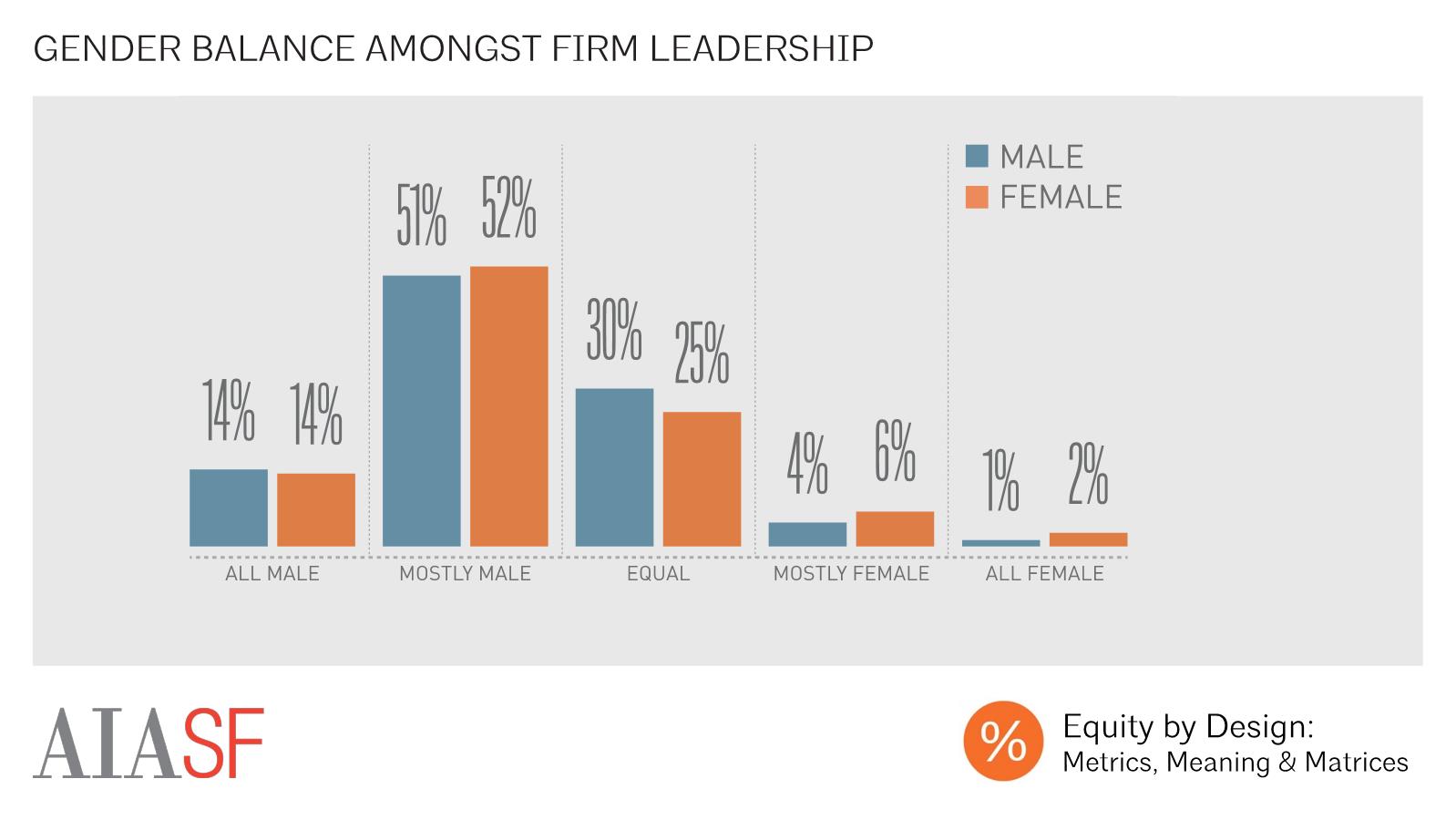

Nearly 40 years after that panel was convened, the glass ceiling is alive and well in the architectural profession. According to the 2016 Equity in Architecture Survey, respondents -- both male and female -- are nine times as likely to work in a firm that was mostly, or entirely, led by men as they were to work in a majority or completely female-led office. While “glass ceiling” was originally coined to describe the challenges that women face, these barriers within the architectural profession hinder people of color as well as women as they strive to attain top leadership positions within the profession. Both of these groups are less likely than white men to be principals or partners in firms at nearly every level of experience. Even though today’s cohort of emerging professionals includes a significant increase in women and an uptick in people of color (although we still have a long way to go before we reach equal representation), the highest rungs of the profession remain pervasively white, and male.

We need to think seriously about the implications that this imbalance at the highest levels of practice might have on the future of the profession. Are we mentoring and training emerging leaders in an equitable manner? Are we restructuring our promotion processes to identify and mitigate the effects of implicit bias? In short, are today’s leaders taking the necessary steps to advance the interests of all employees by fostering a management culture that champions equitable and just practices to achieve true diversity and inclusion?

Results from the 2016 Equity in Architecture Survey enable us to begin to answer these questions, and to provide insight into whether there’s a glass ceiling in architecture, and into the ways that each of us might begin to cultivate equitable practices and policies that result in true diversity of representation and thought leadership in our firms. This story has several parallel threads. First, we’ll quantify the leadership gap in architecture – does race or gender matter when considering likelihood of being a firm leader? Are there characteristics of firm leaders’ positions that vary on the basis of race or gender? Next, we’ll examine the importance of equitable representation amongst leadership to all employees – does working in a firm that has a diverse leadership team matter to one’s career perceptions or access to opportunities like mentorship? Finally, we’ll examine pathways to leadership – how does a firm’s review and promotion process correlate with career perceptions? And does ambition vary by gender or race?

Measuring the Glass Ceiling

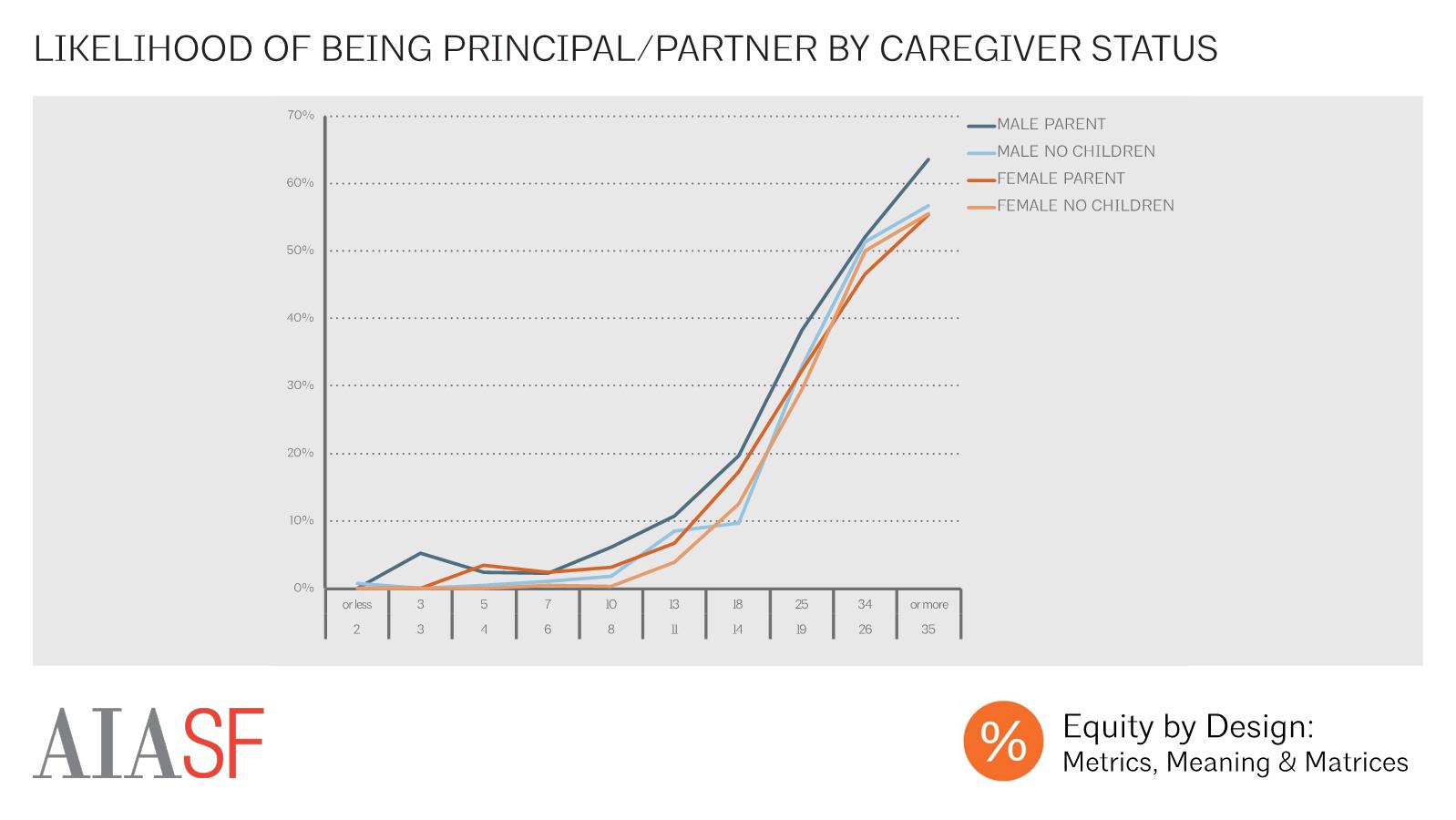

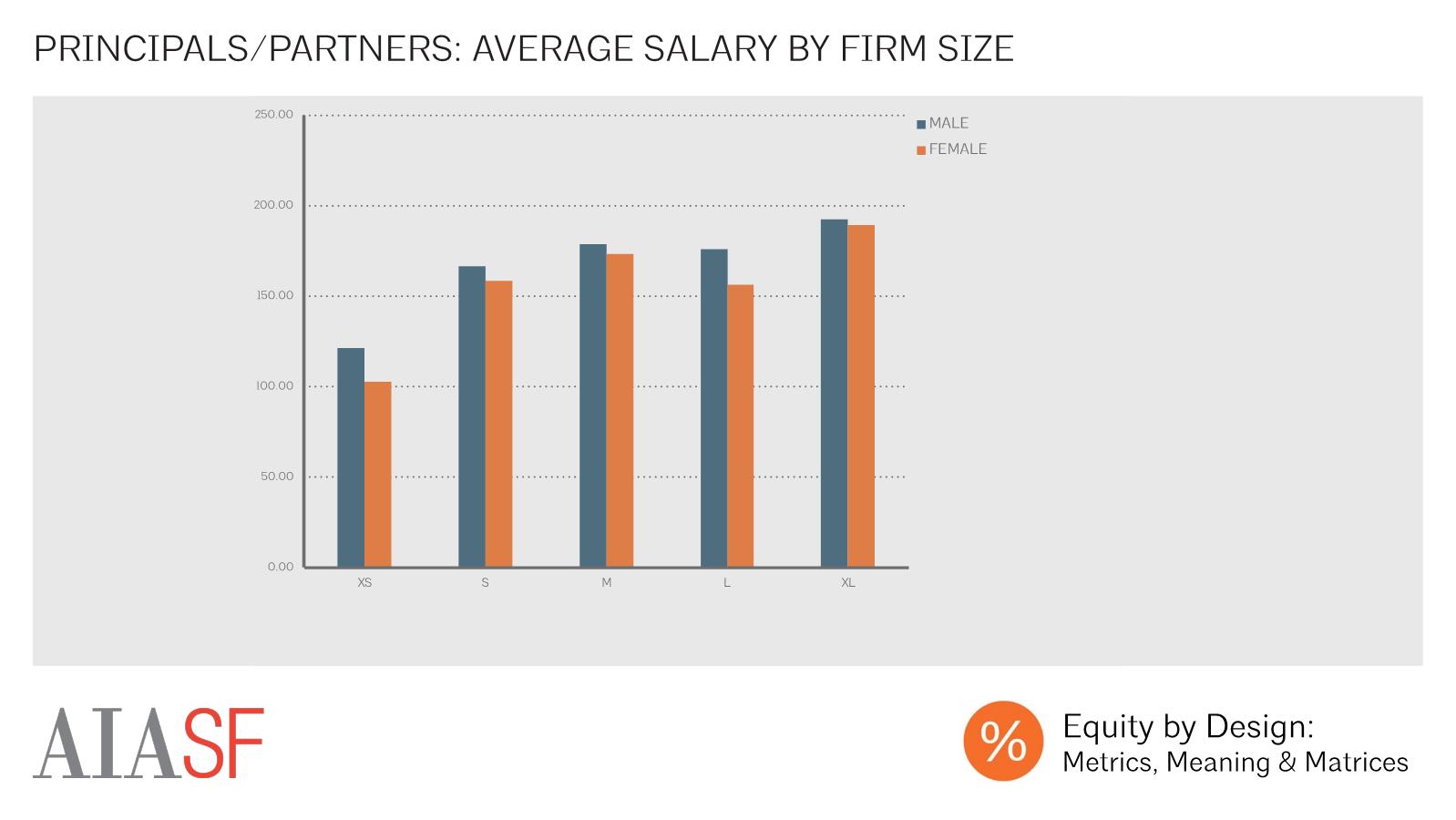

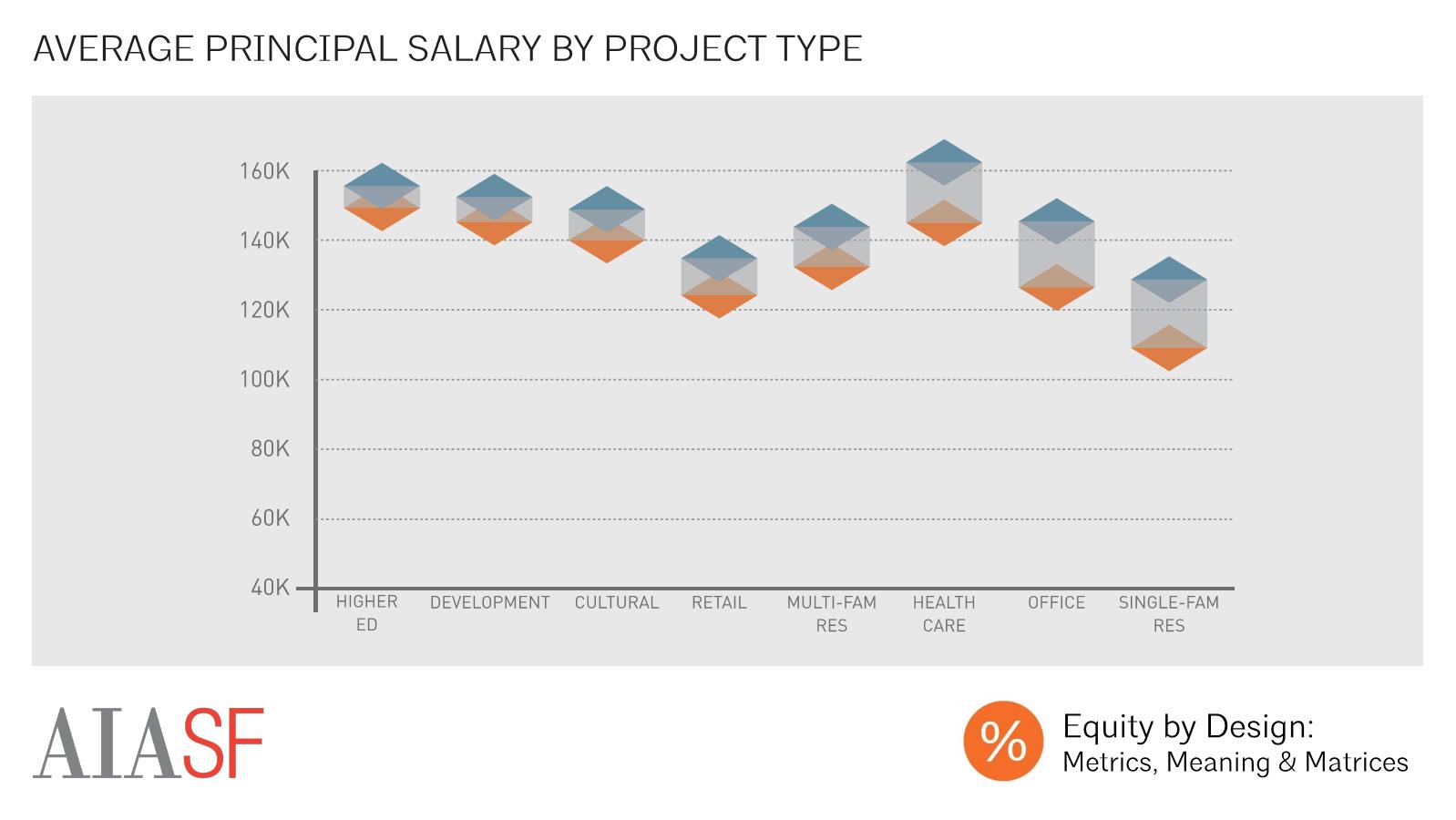

At nearly every level of experience, women and people of color were less likely than white men to hold leadership positions within architecture firms. White men held an even greater advantage over other respondents when only top leadership positions were considered, and were significantly more likely to be principals or partners in firms at almost every level of experience. There were also significant differences between male and female principals’ and partners’ leadership positions, compensation, and experiences. Male principals and partners were more likely to lead larger firms and made more money, on average, than female principals within the sample. While deserving of attention in and of itself, this leadership gap also contributed significantly to differences in men’s and women’s career perceptions. Principals and partners -- both male and female -- had more positive career perceptions on average than those who were not principals in their firms.

The Case for Equitable Leadership

The leadership gap in architecture clearly impacts individual practitioners’ career trajectories, and, in turn, those practitioners’ career perceptions and compensation packages. The survey also demonstrates that the lack of equity within the ranks of firm leadership impacts all employees, and not just those who may have been passed over for a promotion. While the majority of respondents reported working in firms that were mostly, or completely, led by men, respondents working in firms with equal gender representation amongst firm leadership reported more positive career perceptions. Firm leadership composition also proved to be a significant factor in a respondent’s likelihood of having access to senior firm leaders. Both male and female respondents were most likely to have a leader within their office -- either a principal or partner, or their direct manager -- to whom they could turn for career advice in offices with equally divided leadership (72% of men and 68% of women in equally divided offices). This difference in access to leaders is significant because, compared to those who received no career guidance, those who turned to a senior leader within their firm for this guidance were more more optimistic about their professional futures, more energized by their work, more likely to plan to stay at their current job.

Pathways to Leadership

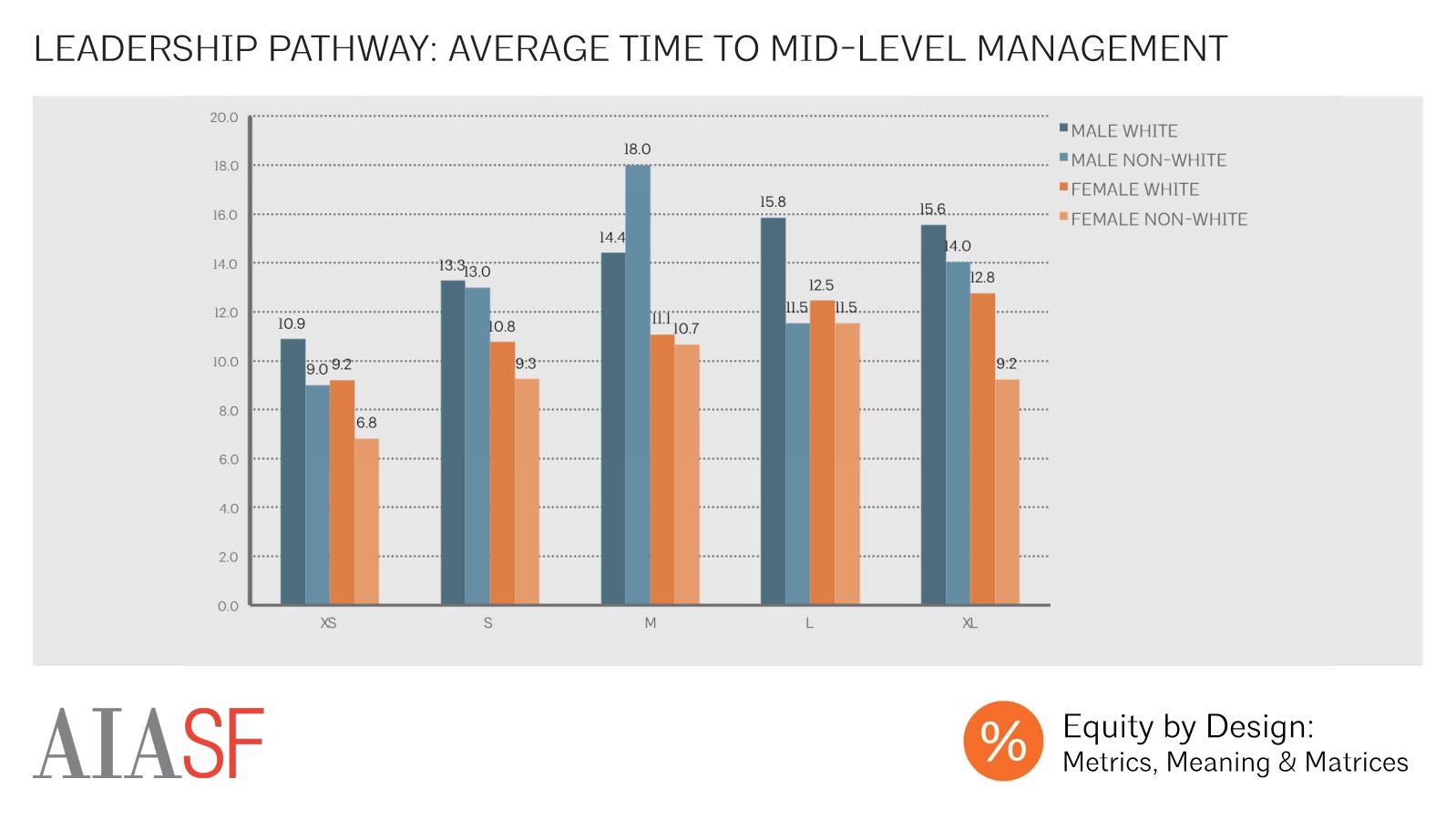

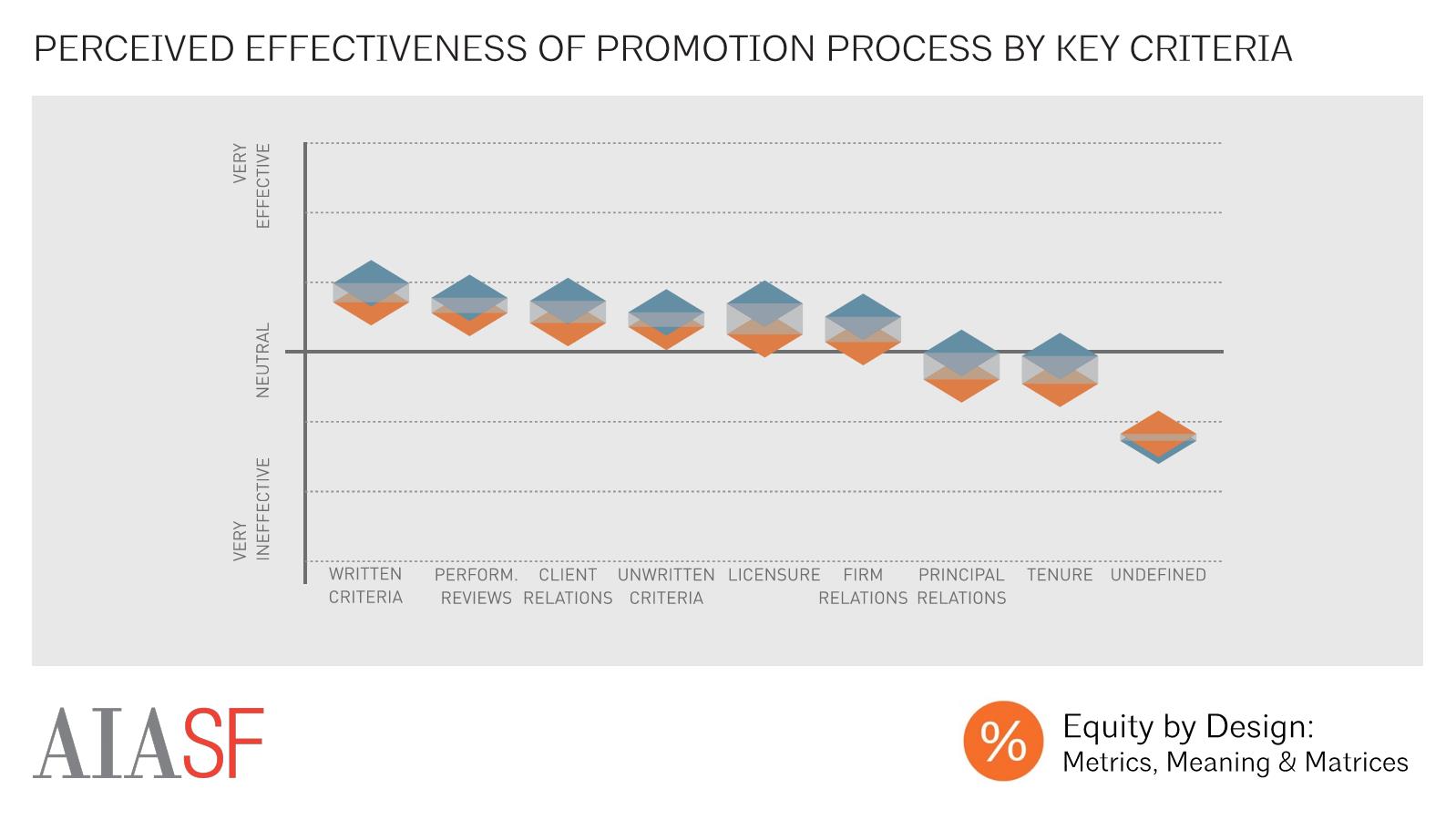

Given the significant race- and gender-based differences in respondents likelihood of advancing into leadership positions, and the significant advantages that were observed amongst those who worked in environments with equitable representation amongst leadership, we were interested in the pathways into leadership positions, and respondents’ perceptions of these processes within their own work environments. We found that, amongst current firm leaders, women and people of color had typically advanced into their leadership positions at the same pace or slightly more quickly than their white male counterparts. This suggests that the pattern observed within other industries, wherein women and people of color tend to advance more slowly than white men, may not hold in architecture. Instead, women and people of color are unlikely to advance at all, but a select number of individuals from these groups are placed along the typical white male leadership trajectory.

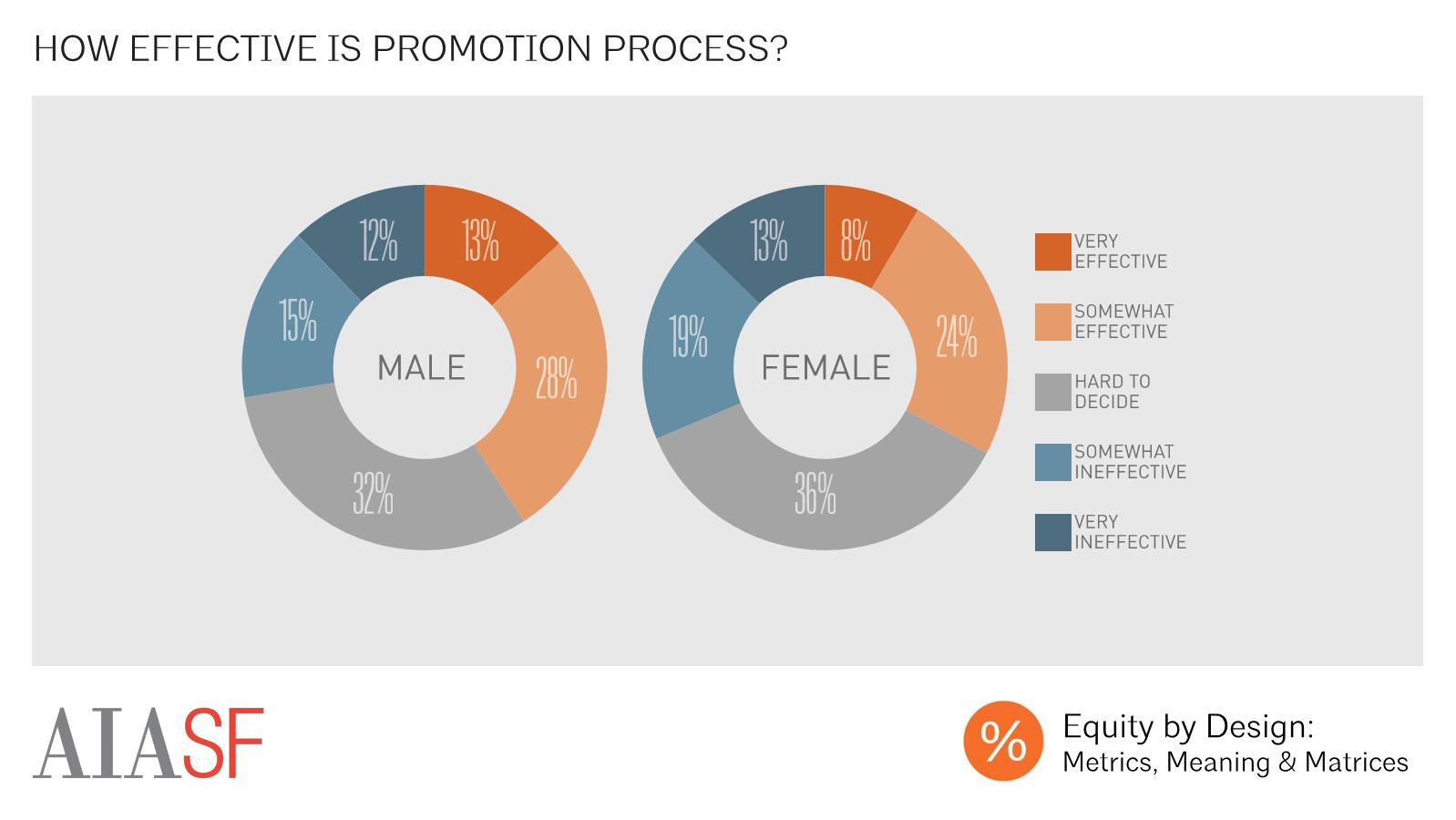

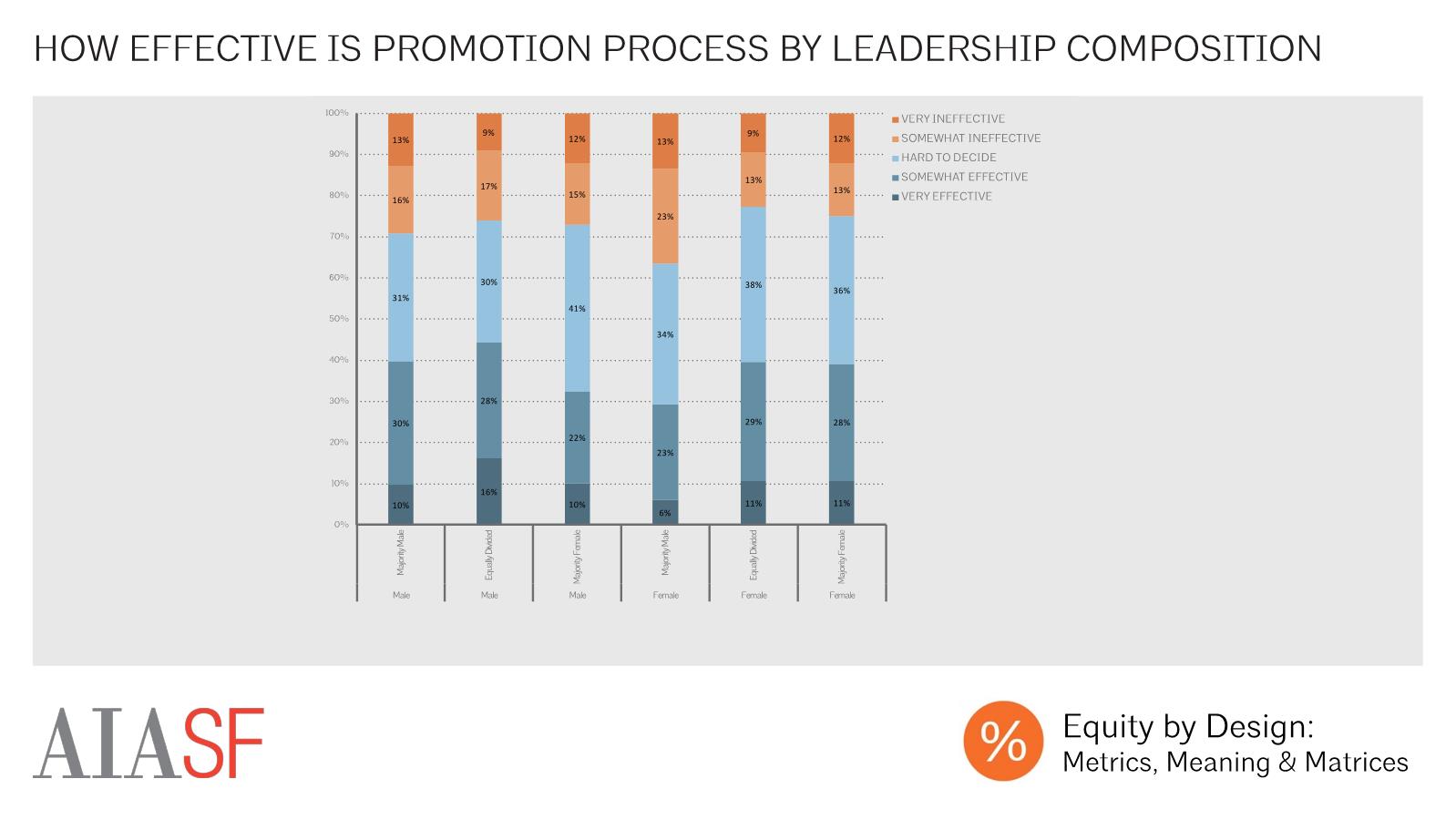

According to Loden’s conception of the glass ceiling, gaps in leadership representation contribute over time to to gaps in perceptions of the promotion process, and eventually, ambition and career optimism. We found similar patterns within our sample. While respondents’ opinions of their firms promotion processes were low overall, female respondents were less likely than male respondents to find their promotion processes effective. This was especially true amongst women working in majority-male-led offices, with only 29% of female respondents working in these settings finding their firms’ promotion processes “very” or “somewhat effective.”

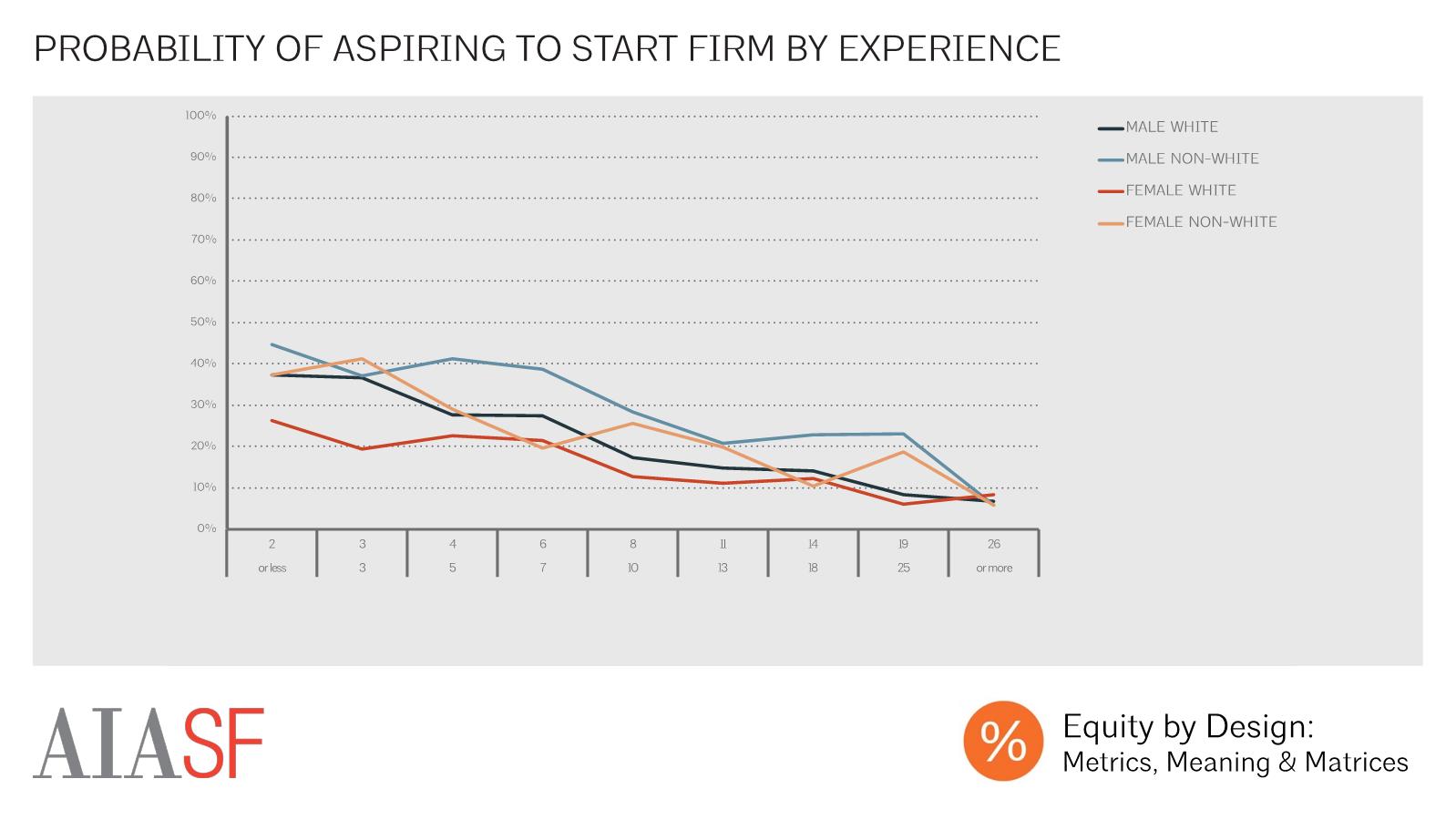

Ultimately, we did observe significant gaps between white male and female and non-white male respondents’ career ambitions, with male respondents more likely to aspire to become a principal or partner -- either through promotion or by starting a firm of their own -- at every level of experience. While there weren’t differences overall in likelihood of aspiring to become a principal or partner on the basis of race, there were significant differences in the ways that respondents aspired to attain these top leadership positions, with non-white respondents more likely to aspire to start their own firms and white respondents more likely to aspire to be promoted to a leadership position within an existing firm.